Was it or Was it Not a Currency War?

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

Former Fed Chair Bernanke has penned a blog post that seeks to refute claims that the US monetary policy was the start of a currency war. Brazil’s finance minister first levied this claim in 2010 as the Federal Reserve, under Bernanke’s leadership, launched a long-term securities purchase program commonly dubbed Quantitative Easing (QE).

Many in the media and the analytic community ran with the currency war concept, much to our dismay. In our work over the last several years, we have been critical of what we thought was a misuse of the concept.

Former Fed Chair Bernanke has penned a blog post that seeks to refute claims that the US monetary policy was the start of a currency war. Brazil’s finance minister first levied this claim in 2010 as the Federal Reserve, under Bernanke’s leadership, launched a long-term securities purchase program commonly dubbed Quantitative Easing (QE).

Many in the media and the analytic community ran with the currency war concept, much to our dismay. In our work over the last several years, we have been critical of what we thought was a misuse of the concept.

Bernanke provides a quasi-official response. His argument is two-fold. The first part in effect claims that the currency war claim is based on incomplete analysis. It is true, he admits, that holding everything else constant, the easier monetary policy in the US would drive the dollar down and boost exports.

However, he quickly notes that there are other moving parts. Not everything else is constant. Specifically the same monetary policy that may weaken the dollar boosts domestic demand by stimulating employment. This lift income and demand for goods and services, some of which will be provided by foreign producers.

According to Fed research the two transmission channels, foreign exchange and the income effect create opposite impulses of roughly the same magnitude. A 25 bp fall in the 10-year yield may boost net exports by 0.15%, but also lowers net US exports by almost the same amount through the income effect.

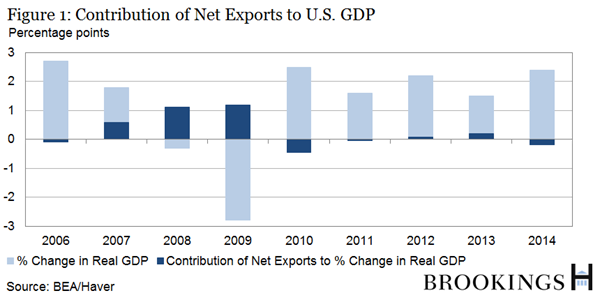

The second part of Bernanke’s argument is a look at the data itself. Outside of a brief period in 2008 and 2009, US net exports did increase, but this was more due to a collapse of imports as domestic demand imploded rather than an increase in exports. Since 2010, net exports have contributed little to US growth and in 2010 and 2014, it was actually a drag.

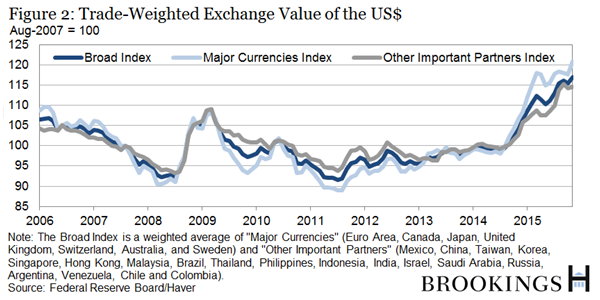

Bernanke scoffs. A currency war by definition requires a currency to weaken. According to various metrics, the dollar appreciated sharply in the second half of 2008, and it proceeds to unwind those gains in 2009-2011. Since mid-2011, the dollar has been appreciating. The pace of appreciation has accelerated since mid-2014.

He provides two charts, which I cut and paste here, to illustrate his points about the role of exports and the dollar’s exchange rate.

Bernanke’s arguments are not going to be the last word on the issue. However, his arguments raise the bar for those who claim the US started a currency war. He says such claims are based on incomplete analysis and are not consistent with the data. His point about the two channels of policy transmission are involved, not just one, likely has broader applicability than just the US.

Bernanke and the Forever (Currency) War is republished with permission from Marc to Market