The End Of Cheap Oil & Its Impact On Financial & Energy Security: Gail Tverberg

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

Historically, many of the world’s major financial crises have been, in some way, connected to the cost or supply of oil. Though numerous countries around the world are now attempting to reduce their oil consumption, the end of “cheap oil” will continue to have ramifications on financial & energy security, particularly in countries such as Greece, Spain, Egypt and India.

Historically, many of the world’s major financial crises have been, in some way, connected to the cost or supply of oil. Though numerous countries around the world are now attempting to reduce their oil consumption, the end of “cheap oil” will continue to have ramifications on financial & energy security, particularly in countries such as Greece, Spain, Egypt and India.

Last week, I gave a talk called Financial Issues Affecting Energy Security at the Advances in Energy Studies conference in Mumbai, India. The general topic of the conference was, “Energy Security and Development – The Changing Global Context.”

As I look at the situation, it seems to me that many of the crises around the world are connected to oil supply and the cost of this oil supply. If oil supply gets tighter, there is potential for these crises to get worse. In this talk, I will also show the connection of oil supply limits to some of the financial crises we see today, and to energy security. I will also show some slides on the Indian oil and coal situation, and explain some connections to world limits.

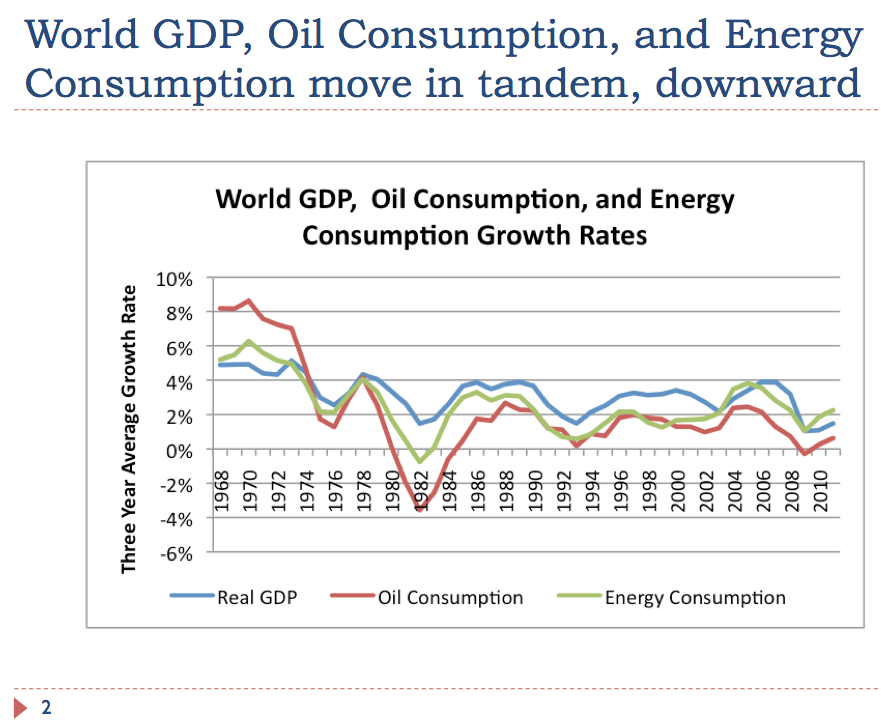

World GDP, oil consumption, and energy consumption tend to move in tandem (Slide 2). While the figures shown above are for the world, the same situation tends to exist for smaller groupings as well. Countries with rapid economic growth tend to use a growing amount of energy, especially oil. This is logical, because making goods and services tends to use energy. For example, growing food and transporting it using modern methods uses oil.

Another reason energy consumption and growth in GDP tend to go together is because workers who earn a salary by making goods or services can afford to buy goods and services using oil and other energy products. For example, they may be able to afford to buy a car or to go on a vacation. People who have lost their jobs have much less to spend on goods and services. This is another reason energy (and oil) consumption tends to be higher when more people have jobs–that is during periods of economic growth.

Countries with little economic growth tend to be ones with little growth in oil consumption, and in energy consumption in general.

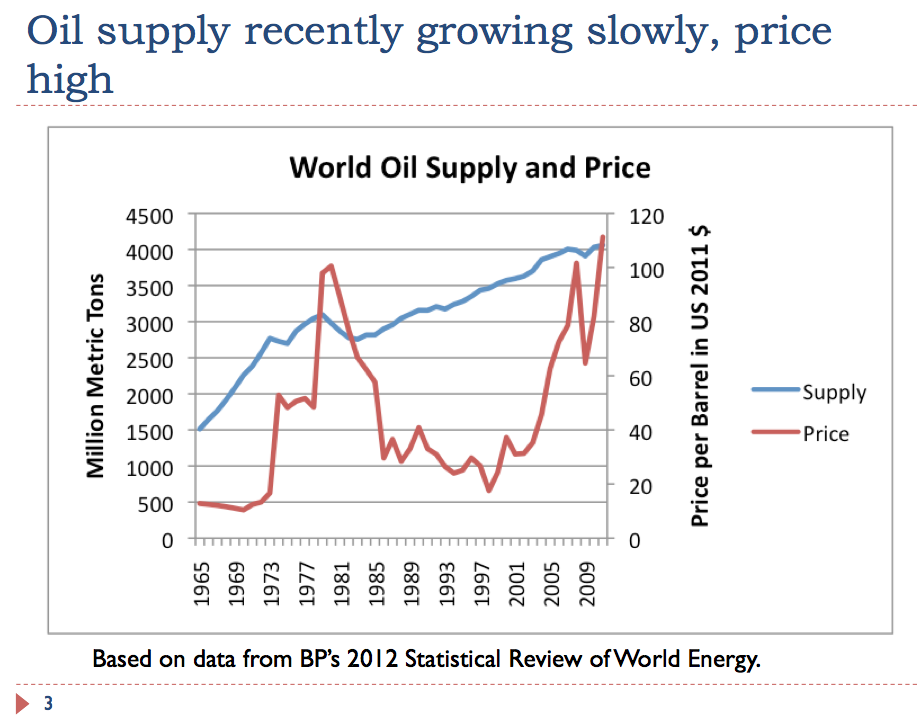

If we look at world oil supply and price (Slide 3), we see that there have been two big price spikes. The first one came in the 1970s and early 1980s, after the oil production of the United States began to fall in 1971. The United States found itself increasingly dependent on imports, leaving the door open for the Arab Oil Embargo. By the mid-1980s, the world got its oil supply problem under control, partly by drilling for oil in new places (North Sea, Alaska, and Mexico) and partly by finding ways to reduce oil consumption (smaller cars; shifting electricity production to coal or nuclear instead of oil).

In recent years, we are facing a second sharp rise in oil prices. This sharp rise really reflects both a “demand” and a “supply” problem:

(1) Demand. World demand for oil started rising sharply after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. China, India, and other Asian countries began rapid economic growth, leading to a greater need for oil and other energy products. Slide 3 shows world supply did not show any unusual “spurt” to meet this demand. Instead prices began to rise.

(2) Supply. To a significant extent, “The easy oil is gone“. What is left in the ground is oil that is both expensive and slow to extract. Two examples of such oil are “shale oil” and bitumen from the Canadian oil sands. Because of high extraction costs, these types of oil need a high sales price to justify their extraction. In fact, a recent report indicates that costs in the Canadian oil sands are soaring. If growth in oil sands production is to continue at forecast levels, oil prices will need to be higher than has recently been the case.

Related: Is Affordable Energy a Myth? – Interview with Ed Dolan

Related: Can We Learn To Live With Higher Oil Prices?: Gail Tverberg

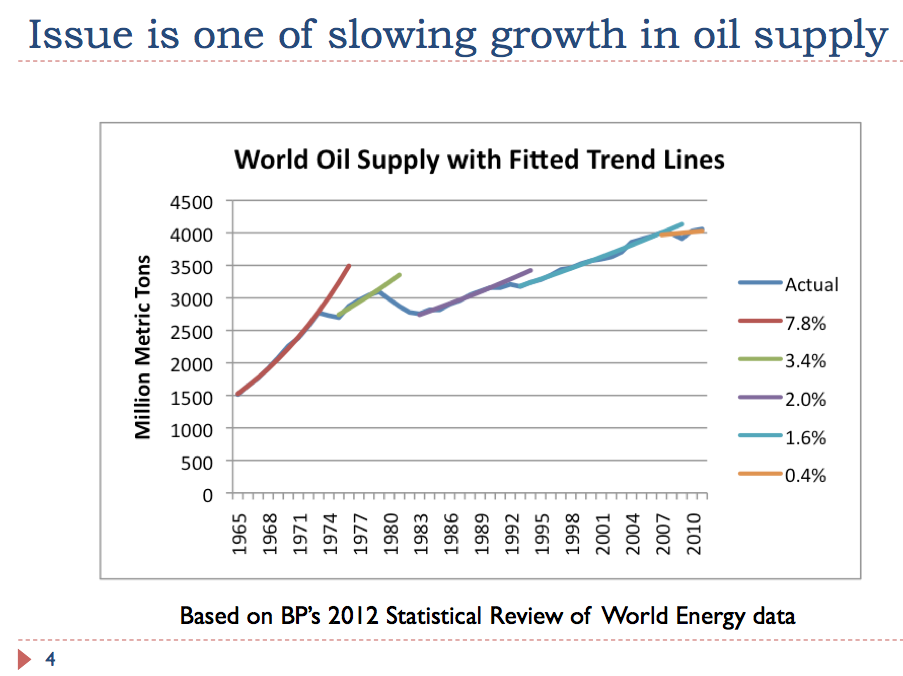

If we look at a graph of growth in oil supply with fitted trend lines, we can see that the rate of growth has in fact been declining over time. This is precisely the opposite of what is needed to accommodate the energy needs of rapidly growing countries such as India and China, and is part of the reason for current high prices.

If we look at world oil consumption divided among three different parts of the world (Slide 5), we see three very different patterns:

(1) European Union, United States and Japan combined. Consumption has fallen since 2005. These are precisely the countries with serious recessions in the 2007-2009 period, when oil consumption was dropping rapidly.

(2) Former Soviet Union (FSU) – Consumption fell when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, and has never recovered.

(3) Remainder (many countries, including China, India, and oil exporters) – Consumption grows rapidly, year after year, even though world supply is not growing by much.

If world oil supply remains relatively flat (as is recently the case on Slide 4), and the growth pattern shown on Slide 5 continues, it is clear that there will soon be a conflict. Either the EU, US, Japan grouping will need to drop their consumption by more, or the “Remainder” group will need to slow down on their consumption, or both. This pattern could mean slower growth for the “Remainder” grouping, or outright recession for the European Union, US and Japan.

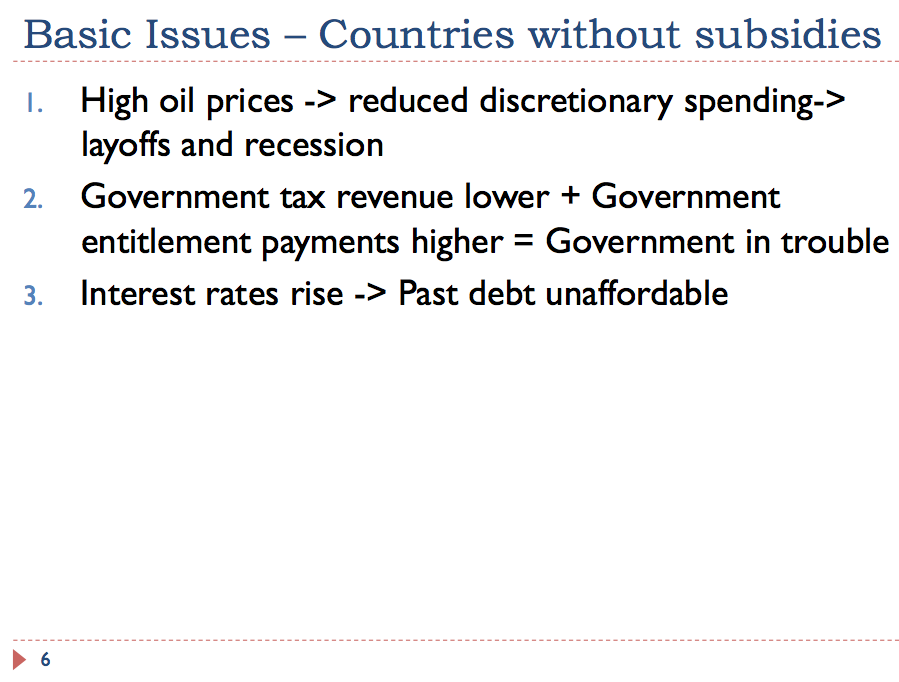

In countries where oil prices are not subsidized, such as the European Union, the United States, and Japan, there are several basic issues:

(1) Because oil prices are not subsidized, higher oil prices are passed through to consumers. These higher prices lead consumers to cut back on discretionary expenses because oil is used for some of the necessities of life, including food production and commuting to jobs. As a result, people in discretionary industries, such as vacation travel, and restaurants, tend to be laid off. There may also be debt defaults, if laid-off workers cannot afford to repay loans. The combination of these factors leads to recession.

(2) Governments are affected, too, because laid-off workers pay less in taxes. Furthermore, laid-off workers often need unemployment benefits and other benefits to mitigate their circumstances. The government may also choose to “stimulate” the economy, or to bail out banks with bad loans. With all of the additional spending and less revenue, recessionary forces get transferred to the governmental sector. This is why so many governments are now troubled with high debt.

(3) In the Euro zone, countries in poor financial condition find it necessary to pay higher interest rates. adding to the country’s financial difficulties. The US has been spared this problem so far, partly because it is viewed as a “safe haven” from Euro problems, and partly because it has the ability to manipulate the level of its currency.

Related: How Energy Consumption, Employment & Recessions Are Interlinked

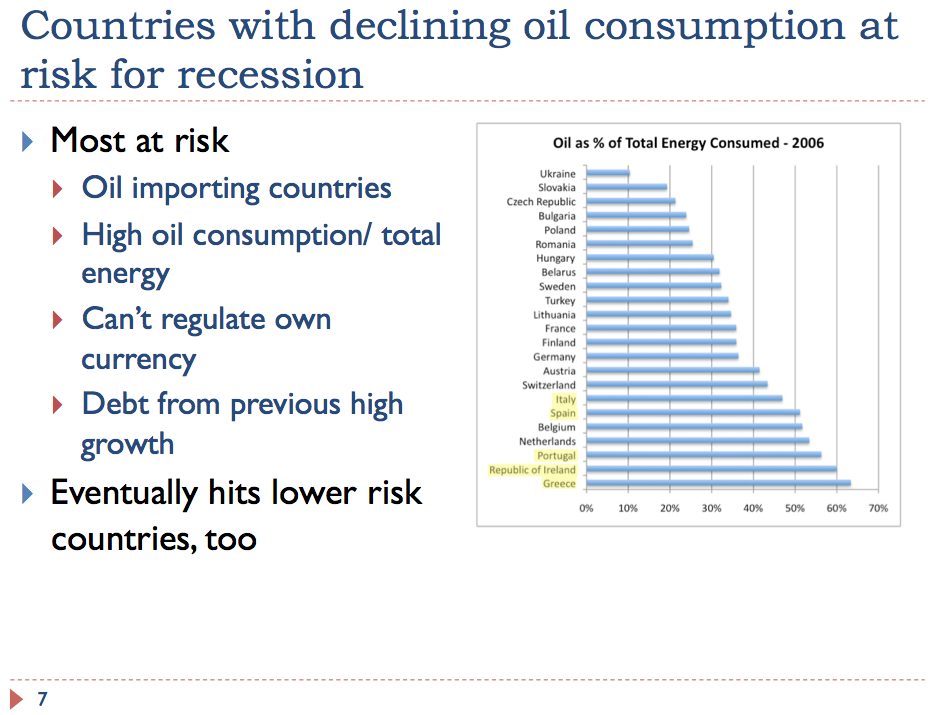

Countries vary in their exposure to high oil prices. Oil importers who get a large share of their total energy from oil (as opposed to other types of fuel) seem to be most at risk. The PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain) tend to be countries using large share of oil in their energy mix. A country which can’t regulate its own currency, such as Greece and other Euro countries is at particularly high risk, because of the problem with higher interest rates mentioned earlier (because these countries cannot drop the value of their currency, to make their exports more competitive).

Eventually, it seems likely that high oil prices will affect all economies, even those of oil exporters. Extra funds from oil exports do not “make their way” to all consumers. So while some parts of an economy may be booming, others will collapse from lack of funds.

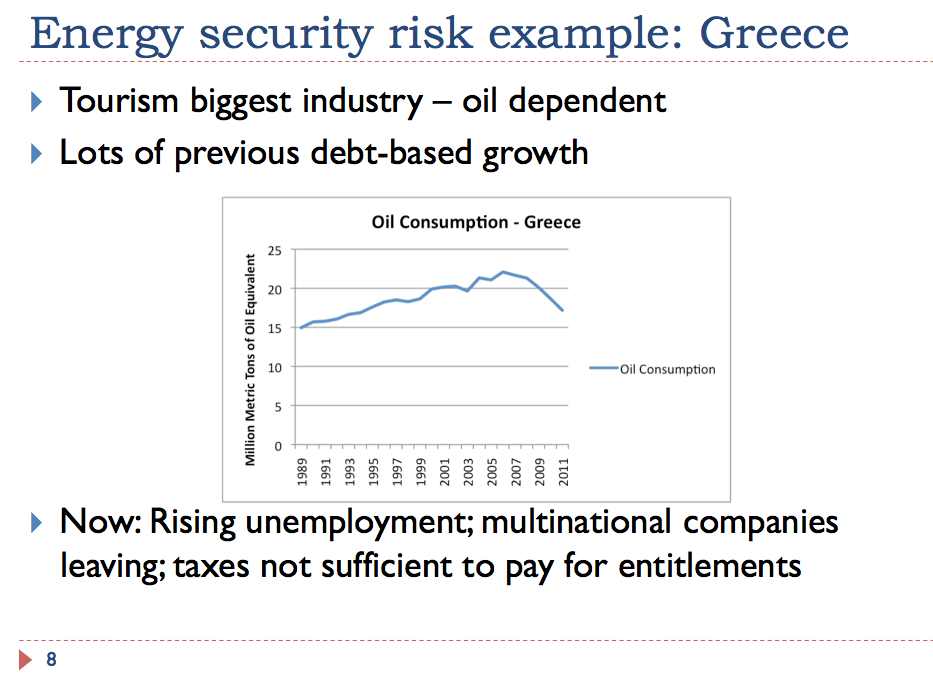

Greece provides an example of the dip in oil consumption that occurs when a country enters a recession. Greece’s largest industry is tourism. High oil prices affect consumers’ ability to purchase vacations in Greece. Large multinational companies (such as Coca Cola Hellenic) decide to move out, for more stability, further adding to the country’s problems. With less investment, the country has an even greater tendency to spiral downward.

Related: Greece’s Fallacious Four – The Main Culprits Of The Greek Tragedy: Mohamed El-Erian

Related: Is Greece Still Headed Down A Dangerous Dead-End Path? : Mohamed El-Erian

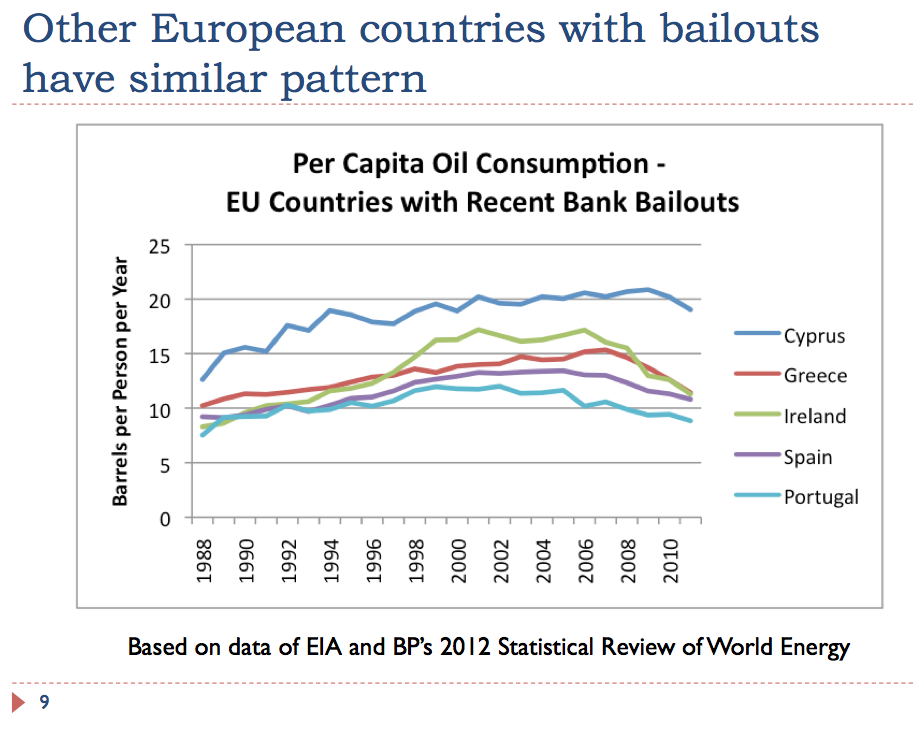

Other European countries requiring bailouts tend to follow a similar pattern to Greece (Slide 9).

So far, we have been talking about countries which don’t subsidize oil prices. How about other countries?

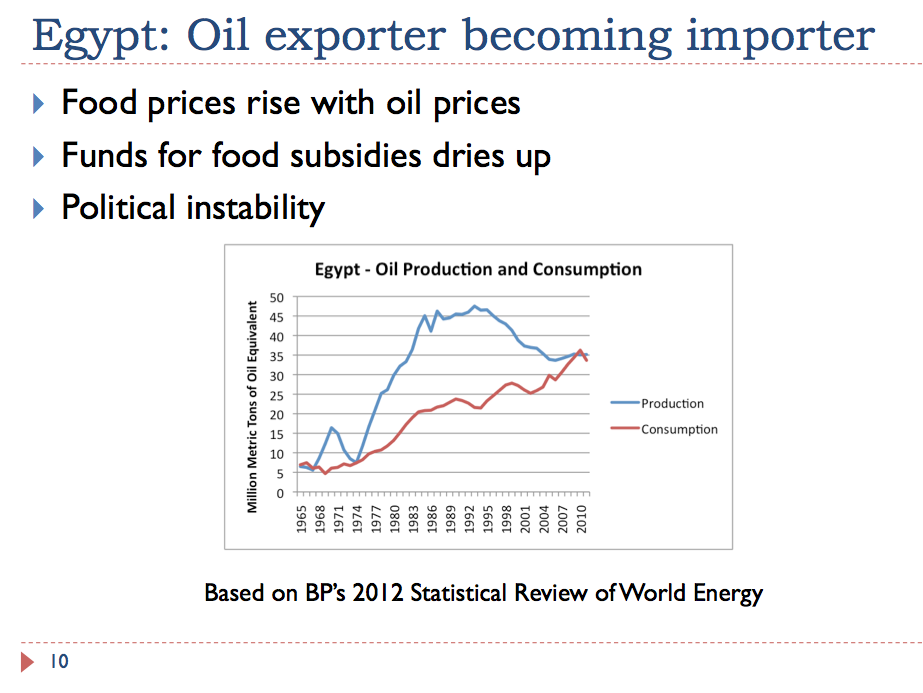

One such country is Egypt (Slide 10). For quite some time, it was an oil exporter. It historically has subsidized both food and oil prices. It has run into problems recently because oil consumption has been rising at the same time that oil production has been falling. Without oil exports to sell, it is very hard to have enough money to fund subsidies of food and oil. Cutbacks in subsidies lead to civil unrest, and the situation starts going downhill quickly. I wrote a post about the Egypt situation earlier, What Lies Behind Egypt’s Problems?

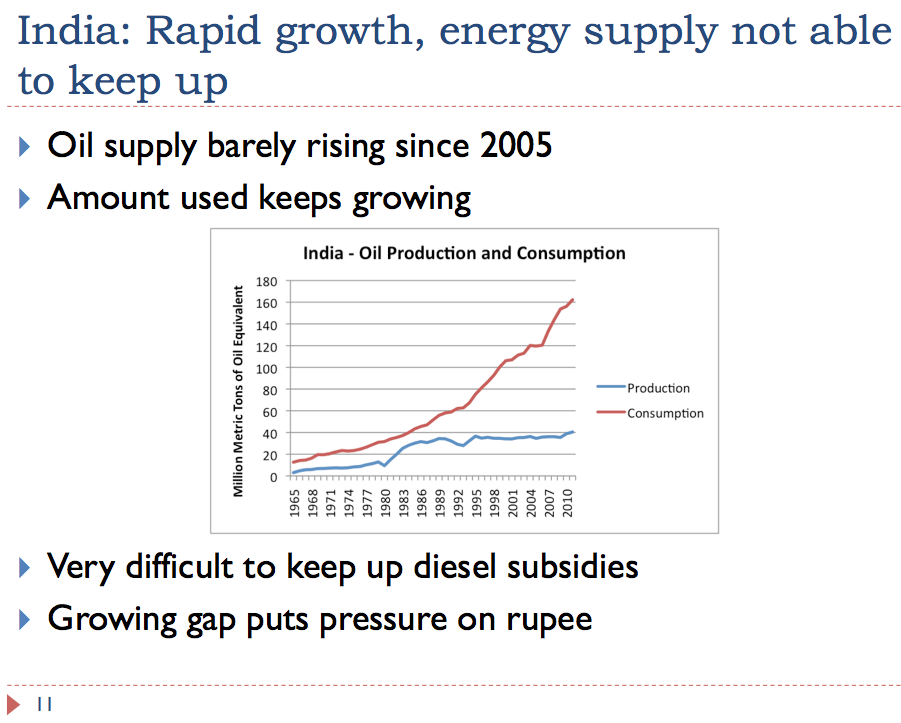

India is not an oil exporter, but it has been subsidizing diesel prices. The graph shown on Slide 11 shows that oil consumption has been rising rapidly, while India’s own oil production has been almost flat. This combination is problematic, because it becomes very expensive to subsidize increasing imports. The growing gap puts pressure on the rupee. It also leads to deficit spending, which in turn leads to a lower sovereign debt rating.

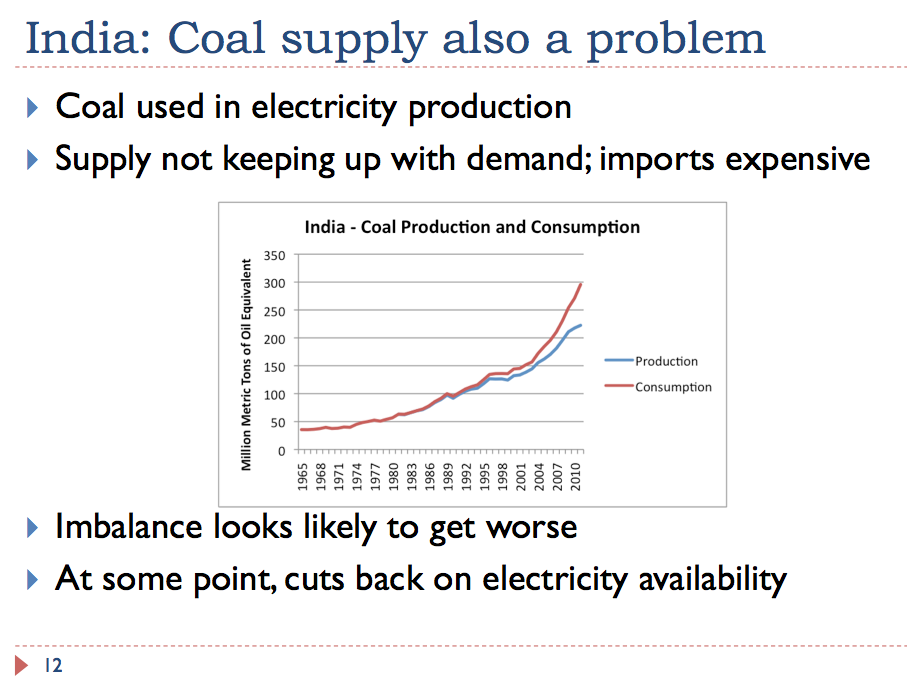

India is now using more coal for generation than it is exporting. Furthermore, the rate of increase in supply and consumption seem to be diverging, with coal production recently becoming much flatter than consumption.

Coal imports cannot be expected to rise indefinitely. China and Europe are both interested in purchasing coal imports, so there is competition for available supply. Also, coal imports tend to be expensive, because of the cost of transport. Coal import costs put pressure on India’s financial condition, just as oil imports do.

Shortages of oil, coal and gas are already taking a toll on India’s economic growth, according to the Wall Street Journal: Grinding Energy Shortage Takes Toll on India’s Growth.

It seems to me that government officials are making plans for the future without really understanding what a limited supply of cheap oil means. What it means, in practical terms, is that governments and citizens will be poorer, rather than richer, in the future. There will be fewer people employed in jobs that require external energy (practically all jobs in Western countries today). Because of energy constraints, wages of most workers will tend to fall in inflation adjusted terms.

Governments will be particularly be affected, because there will be a drop in their tax revenue at the same time that there is more need for governmental services. It will be difficult to keep up pension programs and fuel subsidy programs. The higher cost of fuel (including cooking fuel, where there are subsidies) will mean that consumers will find fuel less affordable. Governments of countries that are particularly affected are likely to be subject to major changes, as citizens become increasingly unhappy with the status quo.

We can look at countries such as Greece to get an idea of the more direct financial security impacts that we can expect. In Greece, we find that high solar feed in tariffs are increasingly a problem, and have recently been reduced. Two electricity companies that rely heavily on natural gas have gone bankrupt. The possibility of rotating blackouts has been mentioned, if the country cannot afford to import high-priced natural gas and oil for electricity. As the highest cost-electricity becomes less affordable, an increasing proportion of electricity seems likely to come from the lowest cost fuel, locally produced lignite.

Also in Greece, non-payment of bills, theft of electricity, and theft of copper wire are already being reported as problems.

In Portugal, China recently bought an interest in the company operating Portugal’s electric grid. The sale was necessitated by the poor financial condition of the company.

Civil unrest is increasingly becoming a problem in countries with shortfalls in affordable energy. Greece. Spain, and Egypt all report civil unrest. If nothing else, such unrest could lead to damage to energy structures, such as electric power plants, including nuclear plants.

As there is more competition for limited resources, the world as we have known it is likely to change. Willingness to accept foreigners into one’s country will decline, if there are not enough good-paying jobs to go around. There will be direct conflict over resources, such as China and Japan’s recent oil dispute.

The Euro zone brought together unequal countries, nearly all of which were short on energy supplies. Now, we are hearing increasing reports about the possibility of the Euro zone’s financial disintegration.

Even within countries, there is the possibility of rich areas wanting to be free from areas which are less well off. We see this dynamic playing out as there are growing calls in Catalonia for independence from Spain.

As countries face the need to cutback, rather than grow, world trade can be expected to decline. In fact, the Wall Street Journal recently reported, “World Trade Volumes Decline for Third Month.” While it is not certain the current dip will continue, this is a pattern we can expect to see again. Conflict between countries, such as we are seeing between Japan and China, can be expected to lead to a drop in trade. The need for austerity measures in countries with financial problems is also likely to lead to a drop in trade.

[quote]While it would be nice to assume “Business as Usual” will continue, and “a rising tide will lift all boats,” these situations look increasingly less likely. What we are instead seeing is that a lowering tide can adversely affect the energy security of many countries at the same time. This is not an easy thought to consider, especially for a country such as India, whose per-capita energy use lags far behind the world average.[/quote]Related: An Alternative Theory For The World’s Limited Oil Supply: Gail Tverberg

Related: Why Oil Prices Stay High – Interview With James Hamilton

Related: Are Global Energy Supplies In Jeopardy? – An Interview With Jellyfish

By Gail Tverberg

Gail Tverberg is a trained casualty actuary who writes about the impact of the limited supply of oil. She speaks internationally about oil issues, and writes frequently about the issue on her blog, Our Finite World and on The Oil Drum (where she is an editor). Tverberg is also a Fellow of the Casualty Actuarial Society and a Member of the American Academy of Actuaries. She has a Masters Degree in Mathematics from the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Financial Issues Affecting Energy Security is republished with permission from Our Finite World.

Get more special features in your inbox: Subscribe to our newsletter for alerts and daily updates.

Do you have a strong opinion on this article or on the economy? We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think by commenting below, or contribute your own op-ed piece at [email protected]