Is the Yuan Really Weak?

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

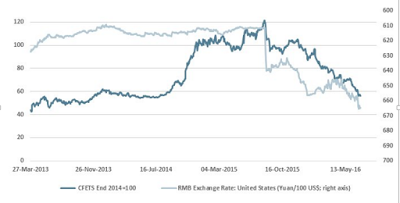

Here are two Great Graphics that portray two time series: the dollar-yuan exchange rate and the yuan against a trade-weighted basket. The first chart comes from a highly reputable consulting firm. It replicates the trade-weighted basket that Chinese officials unveiled and shows how it would have performed in the past.

Here are two Great Graphics that portray two time series: the dollar-yuan exchange rate and the yuan against a trade-weighted basket. The first chart comes from a highly reputable consulting firm. It replicates the trade-weighted basket that Chinese officials unveiled and shows how it would have performed in the past.

The second chart is from Bloomberg. It shows the times series only back to the start of the year. However, the bigger difference is that the second chart indexed the two times series while the first chart shows the two times series with two different scales overlaid to the point that it looks good.

The first chart makes it appear that the yuan has fallen as much against the dollar as it has against its basket. In fact, as the Bloomberg chart makes clear, this is not the case. In the period that Bloomberg has data (January 8 through July 1), the dollar has risen 1.4% against the yuan, while the yuan has lost nearly 5% against its trade-weighted basket.

If the objective is to make a pretty chart, the one from the consultant wins easily. Yet we know of no objective reason why 40 on the index (CFETS) equates to 670 (CNY/100$). If the purpose is to try to understand what the yuan is doing, the Bloomberg chart is more helpful.

The yuan’s depreciation this year has been smaller against the dollar than against other major and Asian regional currencies. The major currencies but the British pound (-12.3%) and the Swedish krona (-1.0%) have appreciated against the greenback so far this year. In Asia, only the Indian rupee (-1.9%) has fallen against the dollar.

What is China doing? Its declaratory policy is for broad stability against the basket. Its operational policy is to tolerate depreciation. Many observers favor one of two explanations. The first is that this was China’s intention all along. After being invited to join the SDR starting in a few months, China has sought a decline in the yuan. The second is Chinese officials are being opportunistic. It responded to the opportunity offered to recoup some competitiveness.

There seems to be another alternative. Facing criticism by the US and IMF, Chinese officials have been more tolerant of the decisions by various economic actors that are weakening the yuan. If the economic forces were driving the yuan higher, a different calculus would be needed.

We suspect that capital inflows of past years are being unwound. This includes corporations paying down foreign currency debt. Foreign investors are small investors in China and yuan assets more broadly. The capital flows are driven nearly entirely by Chinese savers and businesses.

Chinese assets are underperforming this year. The Shanghai Composite has fallen nearly 15%, while the MSCI Emerging Markets equity index has gain 25%. China’s interest rates are flat this year. Market forces are moving the yuan lower. Policymakers seem to be balancing not letting the decline destabilize, while at the same time, seeking to avoid drawing down reserves at a pace that gives investors fright.

Short-term currency movement is important to monitor different pressures and official tactics. However, long-term currency movement may be more important more asset managers. Consider what has happened over the past two years. It was the middle of 2014 that oil peaked and many recognize as the beginning of the dollar’s rally (though in fact, it had bottomed in 2007-2008).

Since early July 2015, the yuan has fallen 7.2% against the dollar. The euro depreciated by nearly 19% and sterling by almost 25%. The Australian dollar lost a fifth of its value. The yen is the only G10 or Asian currency higher against the dollar over this period (~0.2%). Outside of the Philippine peso that has lost essentially as much as the yuan, the other Asian emerging market currencies have depreciated against the yuan.

In the past ten sessions, beginning on June 23 as the UK went to the polls, the yuan has strengthened only once. Despite wider rate interest rate spreads, carry trade strategies remain out of favor. Last year, Chinese officials imposed a substantial (20%) required reserve for domestic banks selling the yuan for clients in the forward market. This appeared to curtail some activity in the onshore-offshore (CNH-CNY) market. Starting August 15, foreign banks will be subject to the same reserve requirement. The required reserves will be held in a zero interest bearing account for a year.

The Court of Arbitration in The Hague will make its first ruling in the numerous territorial disputes in the South China Sea. China has already indicated that it do not recognize the court’s jurisdiction. It will not participate. It will not be bound by the Court’s decision. This does not seem to be a salient factor for investors, though Chinese officials may be concerned about enforcement and/or retaliation.

Great Graphic: The Yuan’s Weakness is republished with permission from Marc to Market