Women At Work: Moving Towards Parity

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

Earlier this month, the former CEO of Yahoo! was unceremoniously removed by the company board, via a telephone call. Many have questioned and wondered if it had anything to do with the fact that Carol Bartz is a woman; if the termination could have been better handled if Bartz were a male.

Of course, there are no straightforward answers.

Earlier this month, the former CEO of Yahoo! was unceremoniously removed by the company board, via a telephone call. Many have questioned and wondered if it had anything to do with the fact that Carol Bartz is a woman; if the termination could have been better handled if Bartz were a male.

Of course, there are no straightforward answers.

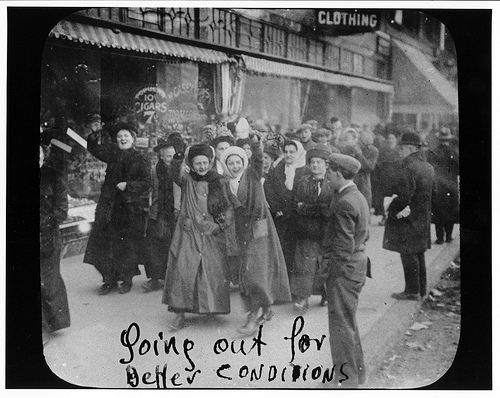

Women have come a long way in terms of social and economic mobility. Several decades ago, women were identified primarily in their traditional sphere of work (i.e., caregiving, within the domains of a home). Education opportunities for females were scarce, much less employment opportunities.

Today, women are showing up in large numbers in universities. Across Ivy League colleges in the United States, the number of female students enrolled are largely equalized. In 2010, 58 percent of all undergraduate degrees in the United States were awarded to women. As a result, women accounted for 53 percent of the total college-educated labour population in the U.S.

The visibility of women in politics, traditionally regarded as a male-dominated sphere, is also increasing. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Margaret Thatcher, the late Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan and Christine Lagarde from the International Monetary Fund are women who have (or had) taken top roles in governments and esteemed international organizations.

Related: The Evolution of Christine Lagarde’s Career

Women have also been a growing factor in the success of the U.S. economy since the 1970s. Indeed, the additional economic contribution of women entering the workforce since the 1970 accounts for about 25 percent of the current U.S. GDP.

Find more economic data from our very own Econ Stats Database.

Yet, despite the advances made in reducing gender discrimination, women still find themselves shortchanged at the workplace. The employment conditions of women are nowhere close to ideal. For years, women have been paid only a fraction of what men earn.

On a more constructive macro level, there is a significant need to raise the labour participation rates of women across global economies. At a corporate organization level, there needs to be more opportunities for women to advance into leadership positions where they can make greater contributions.

The need for female labour inclusion and increased participation goes beyond the issue of gender equality or women’s rights. In fact, to get women in the labour productive force was a calculated economic decision.

Historically, the industrial revolution that transformed Western Europe and the United States had its origins in the introduction of power-driven machinery. During the course of the revolution, non-industrial wage-labour increased, urban centers grew and rural labour markets commercialized.

More importantly, these economic advances coincided with dramatic changes in family life, including a greater role for women in the labour force. Based on a simple resource maximization theory, females accounted for half of the untapped labour reserve pool. Women were increasingly recruited and given independent wages, thereby joining the formal workforce.

Between 1970 and 2009, American women went from holding 37 percent of all jobs to nearly 48 percent. That amounts to almost 38 million more women, without which, the size of the economy would have been 25 percent smaller today.

The point is, GDP growth, the objective of all governments and economic planners, cannot be achieved without two key factors – an expanding workforce and rising productivity.

Achieving a more equitable work environment for women is not an idealized outcome, but an ongoing process. And legislation has been increasingly called in to aid this process.

Structural mechanisms such as extended paid maternity leave, legal protection for women at work and even paternity leave have been introduced to develop women in the workforce.

In Norway, a novel approach has been implemented to break the glass ceiling for women: It is now mandatory that women fill 40 percent of seats on company boardrooms, in a bid to move towards greater gender equality in the workplace.

In a recent McKinsey report about women in the workplace, the findings revealed that “Women don’t opt out of the workforce; most cannot afford to.”

The report goes on to say that “specific barriers that women cite as factors that convince them the odds of getting ahead in their current organizations are too daunting … include: lack of role models, exclusion from the informal networks, and not having a sponsor in upper management to create opportunities.”

Whether positive discrimination is used to take down “artificial” growth barriers for women (in the case of Norway), the key takeaway is more has to be done to address this issue of gender workplace inequality.

While a mandatory policy deciding the ratio of women employed in organizations may be perceived as draconian and difficult to enforce, not to mention going against the principle and cause of equality, more ground level work can be done.

For a start, McKinsey makes a good suggestion here: “Companies can take the lead in refining organizational processes and other formal mechanisms that can encourage compliance to change – in particular the metrics and reporting used to track performance and reinforce accountability.”

Looking forward, it is difficult to discount the contributions made by women in the economy. To increase the contribution of women, more needs to be done about gender relations and functions at the workplace.