Quantitative Hedge Funds = Conventional Economics = BS

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

8 September 2010. David Caploe PhD, Chief Political Economist, EconomyWatch.com

And we don’t mean “Bachelors of Science” – especially since most of the people we’re discussing have at least one PhD, if not more.

While the dominance of computers, and the evident correctness of Moore’s Law – at least until this point –

has obviously been a huge boon to every aspect of mind-based economic pursuits,

it has also brought with it a very evident downside, in two areas above all:

8 September 2010. David Caploe PhD, Chief Political Economist, EconomyWatch.com

And we don’t mean “Bachelors of Science” – especially since most of the people we’re discussing have at least one PhD, if not more.

While the dominance of computers, and the evident correctness of Moore’s Law – at least until this point –

has obviously been a huge boon to every aspect of mind-based economic pursuits,

it has also brought with it a very evident downside, in two areas above all:

stock trading and conventional academic economics – and the two are not unrelated,

especially since each “discipline” began to come under the quantitative influence at about the same time.

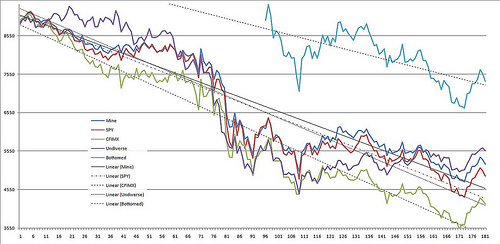

In stock trading, the so-called “quantitatives”, or quants, were revered as the brightest minds in finance,

who could outwit Wall Street with their Ph.D.’s and superfast computers.

But after blundering through the financial panic, losing big in 2008 and lagging badly in 2009,

these so-called quantitative investment managers no longer look like geniuses,

and some investors have fallen out of love with them.

The combined assets of quantitative funds specializing in United States stocks have plunged to $467 billion,

from $1.2 trillion in 2007, a 61 percent decline,

according to eVestment Alliance, a research firm.

That drop reflects both bad investments and withdrawals by clients.

The assets of a broader universe of quant hedge funds have dwindled by about $50 billion.

One in four quant hedge funds has closed since 2007, according to Lipper Tass.

“If you go back to early 2008, when Bear Stearns blew up,

that’s when a lot of quant managers got blown out of the water,”

said Neil Rue, a managing director with Pension Consulting Alliance in Portland, Ore.

“For many, that was the beginning of the end,” he added.

Wall Street’s rocket scientists have been written off before.

When the hedge fund Long Term Capital Management nearly collapsed in 1998, for instance,

some predicted that quants would never regain their former glory.

But this latest setback is nonetheless a stinging comedown for the wizards of high finance.

For a generation, managing a quant fund — and making millions or even billions for yourself —

seemed to be the running dream in every math and physics department.

String theory experts, computer scientists and nuclear physicists

came down from their ivory towers to pursue their fortunes on Wall Street.

Along the way, they turned investment management on its head,

even as their critics asserted they deepened market collapses like the panic of 2008.

Granted, Wall Street is not about to pull the plug on its computers.

To the contrary.

A technological arms race is under way to design financial software

that can outwit and out-trade the most sophisticated computer systems on the planet.

But the decline of quant fund assets nonetheless runs against what has been a powerful trend in finance.

For a change, flesh-and-blood money managers are doing better than the machines.

Much of the money that is flowing out of quant funds is flowing into funds managed by human beings, rather than computers.

Terry Dennison, the United States director of investment consulting at Mercer,

which advises pension funds and endowments,

said the quants had disappointed many big investors.

Despite their high-octane computer models — in fact, because of them —

many quant funds failed to protect their investors from losses

when the markets came unglued two years ago.

And many managers who jumped into this field during good times

plugged similar investment criteria into their models.

In other words, the computers were making the same bets, and all won or lost in tandem.

“They were all fishing in the same pond,” Mr. Dennison said.

Quant funds are still struggling to explain what went wrong.

Some blame personnel changes.

Others complain that anxious clients withdrew so much money so quickly

that the funds were forced to sell investments at a loss.

Still others say their models simply failed to predict how the markets would react

to near-catastrophic, once-in-a-lifetime financial events like Black September 2008 and the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

“It’s funny, but when quants do well, they all call themselves brilliant,

but when things don’t go well, they whine and call it an anomalous market,”

said Theodore Aronson, a quant fund manager in Philadelphia

whose firm’s assets have dropped to $19 billion, from $31 billion in the spring of 2007.

But Mr. Aronson, who has been using quantitative theories to invest

since he was at Drexel Burnham Lambert in the 1970s,

said investors would eventually return.

“In the good years, the money rolled in, so I can’t really complain now about the cash flow going out,” Mr. Aronson said.

“If somebody can give me proof that this is a horrible way to invest,

then I’m going to get out of it and retire.”

Still, some of the biggest names in the business are shrinking after years of breakneck growth.

During the last 18 months, assets have fallen at quant funds managed by

Intech Investment Management, a unit of the mutual fund company Janus;

by the giant money management company Blackrock;

and by Goldman Sachs Asset Management.

Even quant legends like Jim Simons, the former code cracker who founded Renaissance Technologies, have seen better days.

Mr. Simons was celebrated as the King of the Quants

after his in-house fund, Medallion, posted an average return of nearly 39 percent a year,

after fees, from 2000 to 2007.

It was an astonishing run rivaling some of the greatest feats in investing history.

But since then, investors have pulled money out of two Renaissance funds

that Mr. Simons had opened during the quant boom.

After losing 16 percent in 2008 and 5 percent in 2009,

assets in the larger of the two funds have dropped to about $4 billion from $26 billion in 2007.

Ironically enough, that fund is up about 6.8 percent this year,

compared with a loss of about 3 percent marketwide.

In an effort to woo back investors, some quants are tweaking their computer models.

Others are reworking them altogether.

“I think it’s dangerous right now because a lot of quants are working on what I call regime-change models,”

or strategies that can shift suddenly with the underlying currents in the market,

said Margaret Stumpp, the chief investment officer at Quantitative Management Associates in Newark.

The firm has $66 billion in assets under management,

and its oldest large-cap fund has had only two down years — 2001 and 2009 — since opening in 1997.

“It’s tantamount to throwing out the baby with the bathwater if you engage in wholesale changes to your approach,” Ms. Stumpp said.

But many quants, particularly late arrivals, are hunting for something, anything, that will give them a new edge.

Those who fail again may not survive this shakeout.

“What we’re seeing is that not all quants are created equal,”

said Maggie Ralbovsky, a managing director with Wilshire Associates,

which gives investment advice to pension funds and endowments,

according to this article in the New York Times.

And neither, Maggie, are all economists,

especially the ones that ignore the political and historical aspects of economics –

in other words, just about all of them.

Now, the reasons for the “quantitative” domination of academic economics

are just about the same as for their ubiquity in stock trading:

numbers are impressive, especially when you consider the ever-increasing speed and amounts of data

of which even the tiniest computers can now make sense.

But numbers account for only so much of what goes on in the real world,

and the most successful stock traders pay just as much attention to emotion

as they do to numbers when trying to figure out what to do with their money.

The most obviously relevant emotions, of course, are greed –

the desire for more / more / more –

and fear – what are you going to do when you start losing or, in the worst case scenario, face the prospect of losing it ALL.

Which has led a lot of economists to the current weird version of conventional psychology, but –

since that TOO has been mathematized over the last 25 years –

that has only re-doubled the fundamental problem:

the unwillingness to deal with politics and history,

the structures that set the framework and meaning of action.

So while behavioral economics may be a small improvement over purely mathematical economics,

neither begins to acknowledge there are larger structures

within which all people have operated all the time, and always will.

Because, of course, there is a definite drawback in acknowledging

the reality of politics and history in being able to make sense of economic behavior:

losing the certainty that comes from an allegedly / self-styled / so-called “rigorous” approach.

And it’s obvious this certainty provides emotional security, especially when it comes to money –

which is why “quants” of all disciplines stick so militantly to their graphs and equations,

as Margaret Stumpp so simply puts it in the quote just before Maggie’s:

“It’s tantamount to throwing out the baby with the bathwater if you engage in wholesale changes to your approach”

just because something happened that a) you didn’t predict or b) even think would ever happen,

although you might think someone with an open mind would do exactly that

if their previous work had failed to allow the possibility of precisely the sort of major event that DID take place.

Indeed, her attitude is summed up more generally by those who argue above:

“their models simply failed to predict how the markets would react to near-catastrophic,

once-in-a-lifetime financial events like Black September and the collapse of Lehman Brothers.”

The problem, of course, is that anyone familiar with history –

or anthropology or sociology or their systematic combination into medianalysis –

knows it is precisely these so-called / self-styled / alleged “once in a lifetime” events that are what matter,

the moments where history turns, after which life – as the quants are discovering – is never quite the same.

Obviously, this realization is a bit more immediate for traders,

who must deal with the realities of life every day in a way more cloistered academics – especially those with tenure –

can avoid most of the time, and spent most of their effort in doing just that: engaging in the most intense forms of avoidance and denial.

But the simple fact of the matter is that those “once in a lifetime” events DID happen.

And not only did the “quants” in both areas completely fail to predict their possibility,

and make a mockery of those who actually said they could happen,

but we are also all STILL dealing, now, two years later,

with merely the IMMEDIATE effects of those events.

Indeed, I would venture to predict,

we are only JUST beginning to see their medium- and longer-term consequences,

above all, the dreaded moment when the “other shoe” –

namely, those “financial weapons of mass destruction,” the derivatives – begin to fall.

And when that happens, just as with their correlatives in the world of physics,

there are likely to be both immediate “blast effects” and then longer-term “fallout.”

Once those strike, you can be pretty sure that,

while the quants of both stock trading and conventional economics

will be sure they can tell us the exact dimensions of the mess into which we will have fallen,

it would seem to be wise to take those predictions with a ton of salt as well.

Because it’s pretty unlikely any of them ever thought “it would actually come to this.”

David Caploe PhD

Editor-in-Chief

EconomyWatch.com

President / acalaha.com