Paradox of Thrift: Hoarding Cash In Corporate America

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

Apple created a stir last month when it revealed figures showing that it had cash equivalents and marketable securities of about US$76.2 billion. Likewise, General Electric boasted cash holdings of US$136.3 billion on its balance sheet for the last financial year, significantly more than the US$73.8 billion of operating cash balance held by the United States Department of Treasury at the end of July.

Apple created a stir last month when it revealed figures showing that it had cash equivalents and marketable securities of about US$76.2 billion. Likewise, General Electric boasted cash holdings of US$136.3 billion on its balance sheet for the last financial year, significantly more than the US$73.8 billion of operating cash balance held by the United States Department of Treasury at the end of July.

In a similar vein, Google recently announced that it plans to purchase the mobile handset arm of Motorola, Motorola Mobility, for US$12.5 billion. In the largest deal to date, Google would pay out US$40 per share in cash, at a 63 per cent premium over Motorola’s last trading price during the mid-August deal announcement.

Companies like Google and Apple, who are sitting on large piles of cash reserves, are not anomalies. Moody’s Investors Service recently reported that nonfinancial companies in emerging Asian markets were holding onto an estimated US$230 billion in cash. Similarly, in a February address to the Chamber of Commerce, U.S. President Barack Obama said,

[quote]“Today, American companies have nearly $2 trillion sitting on their balance sheet.” [/quote]There are good reasons to find more cash on the balance sheet than financial theories suggest prudent. On the surface, ample corporate reserves provide a certain level of financial buffer during economic slumps, especially when lending is tightened. Similarly, a company’s persistent and growing reserve often signals strong financial performance.

Yet, financial institutions still have to address the need to balance liquidity considerations and the pursuit of revenue growth.

Sitting on cash can be an expensive luxury simply because it incurs a heavy opportunity cost. Holding onto excess cash that is beyond reasonable liquidity requirement is not only capital inefficient; it also creates a drag on a company’s valuation.

In particular, the massive cash hoards that American corporations have amassed have been a saving grace in ensuring that the financial crisis did not cause additional damage to the economy.

Today, these companies are sitting on US$1.93 trillion in cash and other liquid assets, rather than using this money in rebuilding its battered economy.

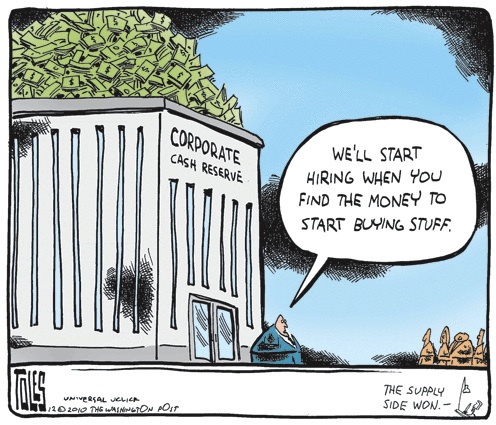

The deep cash pile reveals the strained caution that many companies feel about investing, especially in a time where economic recovery is painfully slow and weak consumer spending data continues to shadow high unemployment figures. Besides generating very low returns on this untapped reserve pool, the cash buildup is also, within good reason, because there are relatively few investment opportunities available.

In short, businesses seem to be playing out what Keynes’ described as the paradox of thrift.

However, that is not to say that the money flows should remain stagnant. Corporate America has, at hand, many ways to deal with the excess liquidity on their book balances. Among them, boosting dividends.

For S&P 500 companies, 255 increased their dividends in 2010, with companies paying an additional US$20.6 billion a year in dividends. According to S&P, two-thirds of companies are forecast to pay more in dividends this year.

At the same time, companies have also been buying back their own stock, in a bid to concentrate each stakeholder’s profit share. According to Howard Silverblatt of S&P, about 45 companies in S&P5 500 have bought back so much stock that their earnings per share will see a boost of about 5 percentage points.

However, a key concern over such liquidity management strategies is that it does not redistribute wealth efficiently. In particular, such moves are not able to create any spillover effects, or generate positive externalities, that would aid in the long run economic recovery – something that both businesses and consumers desperately need.

Likewise, U.S. President Barack Obama has called for businesses to start investing and hiring, and he is not alone in this call.

According to Mihir A. Desai, professor of finance at the Harvard Business School, businesses need to be “goaded into” spending their reserves, in a manner that “the economy could benefit from a significant stimulus that, unlike measures relating to a government spending, would stem from decentralized actors responding to private information and incentives.”

In that way, it would be more efficient and optimal at addressing the fundamental needs of the economy, such as the persistently high levels of unemployment.

American consumers seem to have run out of confidence while businesses are cautious and playing their cards close to their chest. The Fed too, seems to have run out of stimulus arsenal.

Desai, however, believes that the government has one last bullet in their fiscal arsenal – to impose a temporary tax on excess cash holdings to stimulate spending. According to Desai, this has to be done ideally in conjunction with repatriation tax holidays and a reduction in corporate tax for the “carrot and stick” incentive scheme to work.

[quote]“A gentle nudge to break this coordination failure could shake managers out of their indecision and provide a privately-directed, revenue-neutral stimulus that could eclipse the effects of any potential stimulus that could emerge from Washington today,” he said. [/quote]