Nigeria’s Smuggling Problem: A Self-Inflicted Wound?

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

In 2012, customs sources say that Nigeria lost nearly $200 million in potential tax revenues to rice smuggling. Added to the annual losses from oil and other forms of commodity smuggling, Nigeria may be losing billions each year through its borders. But while the government is spending millions in order to secure its borders, perhaps it should look at its own trade policies, which may have encouraged the rampant smuggling in the first place.

If you follow business and policy in Nigeria you have probably heard this story before:

In 2012, customs sources say that Nigeria lost nearly $200 million in potential tax revenues to rice smuggling. Added to the annual losses from oil and other forms of commodity smuggling, Nigeria may be losing billions each year through its borders. But while the government is spending millions in order to secure its borders, perhaps it should look at its own trade policies, which may have encouraged the rampant smuggling in the first place.

If you follow business and policy in Nigeria you have probably heard this story before:

We are being driven out of business by cheap imported products. If care is not taken the whole local industry will collapse and we will lose thousands of jobs. The government should ban these imports or at least place tariffs to support our local industry and help keep these jobs.

There is another variant of the story centred on kick-starting local industry but the gist is the same. The government usually responds with something along the lines of an outright ban or at least some kind of increase in tariffs on these imported goods. The imported goods become more expensive for a while, local producers get some temporary relief and everyone is happy…until the story changes:

We are being driven out of business by cheap imported products smuggled into the country. If care is not taken the whole local industry will collapse and we will lose thousands of jobs. The government should secure our borders and help keep these jobs.

Now the government would probably like to respond by securing the borders, but that is a bit more difficult.

To understand just how difficult it is we should take a trip to a parallel universe. In this parallel universe the western border of Nigeria is actually 100km east of where we think it is. Turns out in this universe, Ibadan, Badagry, and Abeokuta are all in the Benin Republic. Now in this parallel universe, if the government of Nigeria decided that it wanted to stop some goods from flowing from Ibadan to Ekiti, or from Badagry to Akure, how possible do you think that would be? It may not be impossible but it would still be highly improbable, or at the very least extremely expensive to try.

Now teleport back to our universe where the western border is as we know it. This time the same government is trying to control the flow of goods between Cotonou (in Benin) and Lagos, or between Parakou (in Benin) and Ilorin. How likely is it that the government will successfully be able to restrict trade? Again, it would probably be the same conclusion as before – unlikely and very expensive to try.

[quote]The thing is the border between Nigeria and Benin is really just a line on a map. Trade between these areas has gone on for so long and at such scale that it is near impossible for any agency to control it. The same can also be said for Nigeria’s northern borders with the Niger Republic and the Eastern borders with Cameroon to some extent.[/quote]It is not surprising then that government actions to manipulate prices of goods in Nigeria, either through tariffs to artificially raise prices of imports or subsidies to artificially lower locally produced goods, have almost always led to smuggling of such goods. For instance, if the government forced the price of a litre of fuel in Lagos to be N65 but the same fuel sold at N150 a litre in Cotonou, you don’t need to have a Harvard MBA to see the opportunities there.

The potential profit by smuggling fuel across the border far outweighs any cost if caught. A Central Bank of Nigeria governor even once claimed that with the kind of margins being earned, he could potentially bribe every customs agent along the way. For regular citizens, who have been trading for centuries with their neighbours, a few laws are unlikely to stop from taking advantage of these opportunities and making lots of money.

Related: Nigerian Oil Theft Reaches $6bn Annually

Related: Shell May Shut Nigerian Oil Pipeline After “Unprecedented” Levels Of Thefts

Related: Infographic: The Black Market, The Second Largest Economy In The World

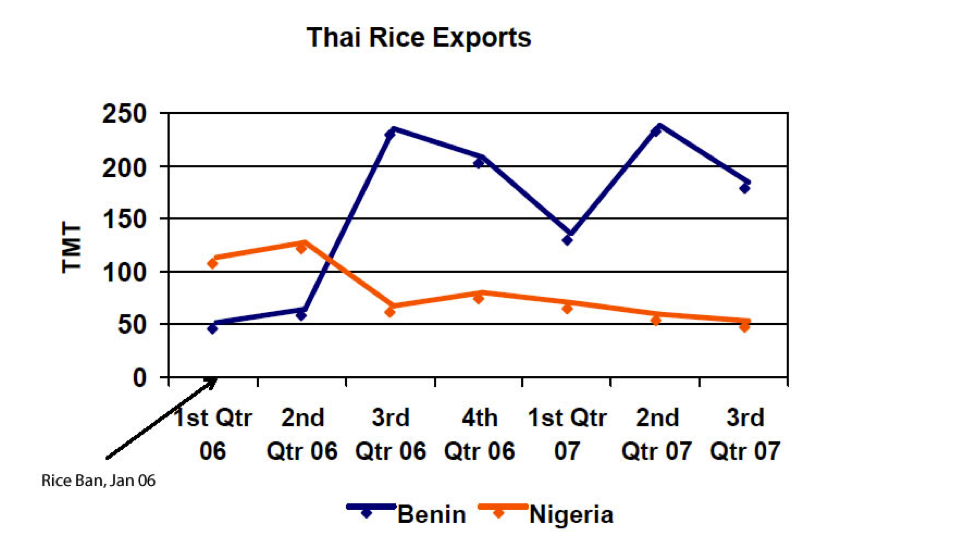

Perhaps the biggest example of the perverse nature of bad trade policy is what happened when imported rice was banned in 2006. The price of imported rice in Lagos quadrupled but the price in Cotonou, where there was no ban, remained relatively fixed. No prizes for guessing what happened next.

Benin Republic went from importing half as much rice as Nigeria to importing almost four times the amount in the following quarters. We know where all that rice ended up. Of course Nigeria could have “secured the border” to prevent that from happening. However we already know how that would have ended.

Image source: http://www.fas.usda.gov/gainfiles/200711/146292904.pdf

So what is the point of all this?

[quote]This is the point; implementing any kind of trade or price control policy without cooperating with our neighbours is unwise. The presence of alternative markets will probably render any restrictive trade policy useless. [/quote]Related: Are Bad Habits Stifling Africa’s Economic Potential?

Related: Lessons From Georgia: How Nigeria Can Overcome Its Culture of Corruption

Cooperation with Benin Republic, Niger Republic and Cameroun is essential to any successful trade policy in Nigeria. Cooperation that eliminates cross border price differences and does not create perverse incentives will probably lead to better results.

Also yes I deliberately left out the effects of the famous duty waivers. That is a political story for another day.

By Dr. Nonso Obiliki

Dr. Nonso Obikili is a policy associate at Economic Research Southern Africa and was formerly a Lecturer at the State University of New York at Binghamton. His research interests focus on Economic History, Development and Macroeconomics in Africa. The opinions here do not represent the views of his employer.

Rethinking Trade Policy is republished with permission from PolicyNG, Nigeria’s foremost policy analysis platform. Follow them on twitter: @PolicyNG.

Get more special features in your inbox. Subscribe to our newsletter for alerts and daily updates.

Do you have a strong opinion on this article or on the economy? We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think by commenting below, or contribute your own op-ed piece at [email protected]