Food Prices Are Soaring Worldwide – Here’s Why and What Comes Next

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

Global food prices are rising along with many other commodities and constitute a major part of the inflation picture.

According to UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s biannual global food outlook, prices had risen by 40% in the 15 months to June and the trend has continued. That is the largest increase since 2010-11, which students are geopolitical events will know was one of the major triggers of the so called Arab Spring that red to a revolution in Egypt and upheaval elsewhere.

Now the latest data from the FAO shows prices up 30% in the past 12 months alone.

In other words, high food prices is not just an economic problem but a social one. And it is even more of a problem – economically and socially – in developing countries, where people spend proportionally more of their income on food.

Food price inflation threat to economic recovery

As with energy price inflation, food costs could also prove to be a hindrance to maintaining the economic recovery in the wake of the Covid pandemic. That’s certainly the view of JpMorgan. It expects to see a purchasing power squeeze on households” and expects the drag on the recovery to persist into next year.

Food and energy prices are excluded from core inflation data because they can be more volatility, affected such things as the vagaries of the weather in the case of food, and so can have distorting effects on inflation. But for ordinary people, such methodological niceties have no bearing on the real inflation that they are experiencing.

But in addition to weather and climate, food supply is being disrupted by the same supply chain dislocation that is hurting in non-agricultural sectors such as manufacturing.

Climate change and droughts hurting food production

We should also add too that the vagaries of weather and climate may become something more systemic as feared in the droughts that are affecting many key agricultural regions of the global economy, such as Brazil and California.

Droughts in Latin America are particularly severe and the agricultural powerhouse Brazil is in the eye of the storm.

Brazil is facing its worst drought in 91 years, hitting both the agriculture sector but also the extensive hydroelectric power. Hydro power generation is down by 35% in a country where 70% of electricity comes from that source. Beef prices in Brazil are up 43%. The weakness of the Brazilian Real (BRL) is not helping matters – encouraging demand for its exports while making imports more expensive.

Argentina – the largest grower of soya bean – has seen the harvest drop by 10%. Fodder for cattle is in short supply, helping to push beef prices. As the global economy responds to a surge in demand as lockdowns are ended in Western countries, oil and gas prices have risen accordingly.

In Paraguay the Paraná River is 10 feet below its normal level. That’s a huge problem for Paraguay because it is the main transport conduit in the land-locked country – 85% of foreign trade is conducted on the river. In Mexico, 70% of the country is suffering from drought and Mexico City is threatened by a lack of water supply. The country’s central bank blames the drought for adding to inflation.

Not all the fault of the Covid but it played its part

Food inflation in fact began to take root before the pandemic kicked in. Take the example of pork prices in China, the largest consumer of the meat in the world.

In 2018 swine fever hit the country, decimating the hog herd, which amounted at the time to half of the world population of pigs. That had a huge knock-on effect globally by sending pork prices in China through the roof, which in turn pushed up pork and other animal protein prices across the world.

Lockdowns wreaked havoc with supply chains, putting pressure on prices. Also, habits started to change, with less people eating out and more groceries being bought for home consumption i addition to outbreaks of hoarding and stockpiling but a significant number of consumer, led to more upward pressure on prices.

The US is one of the world’s major exporters of food, from cereals to orange juice and the appreciation in the value of the US dollar didn’t help matters for non-dollar buyers. Prices topped out in April 2020 and had begun to moderate by summer 2020, so this changing consumption patterns and the lockdowns can'[t by themselves account for the food inflation.

According to analysis by the IMF, although food prices may be rising at your grocery store and supermarket, that is not yet contributing to headline inflation, but they expect it may do so next year. However producer prices are a different – these had spiked in the first half of the year, although this can take six to 12 months to flow through into consumer food prices.

So where is the major driver right now for the food prices increases consumers are seeing show up in their shopping bills? Shipping costs.

We already know about the driver shortages that had started to impact the supply of petrol to pumps in the UK fuel crisis, worsened by panic buying. But the shipping on the high seas is the big picture.

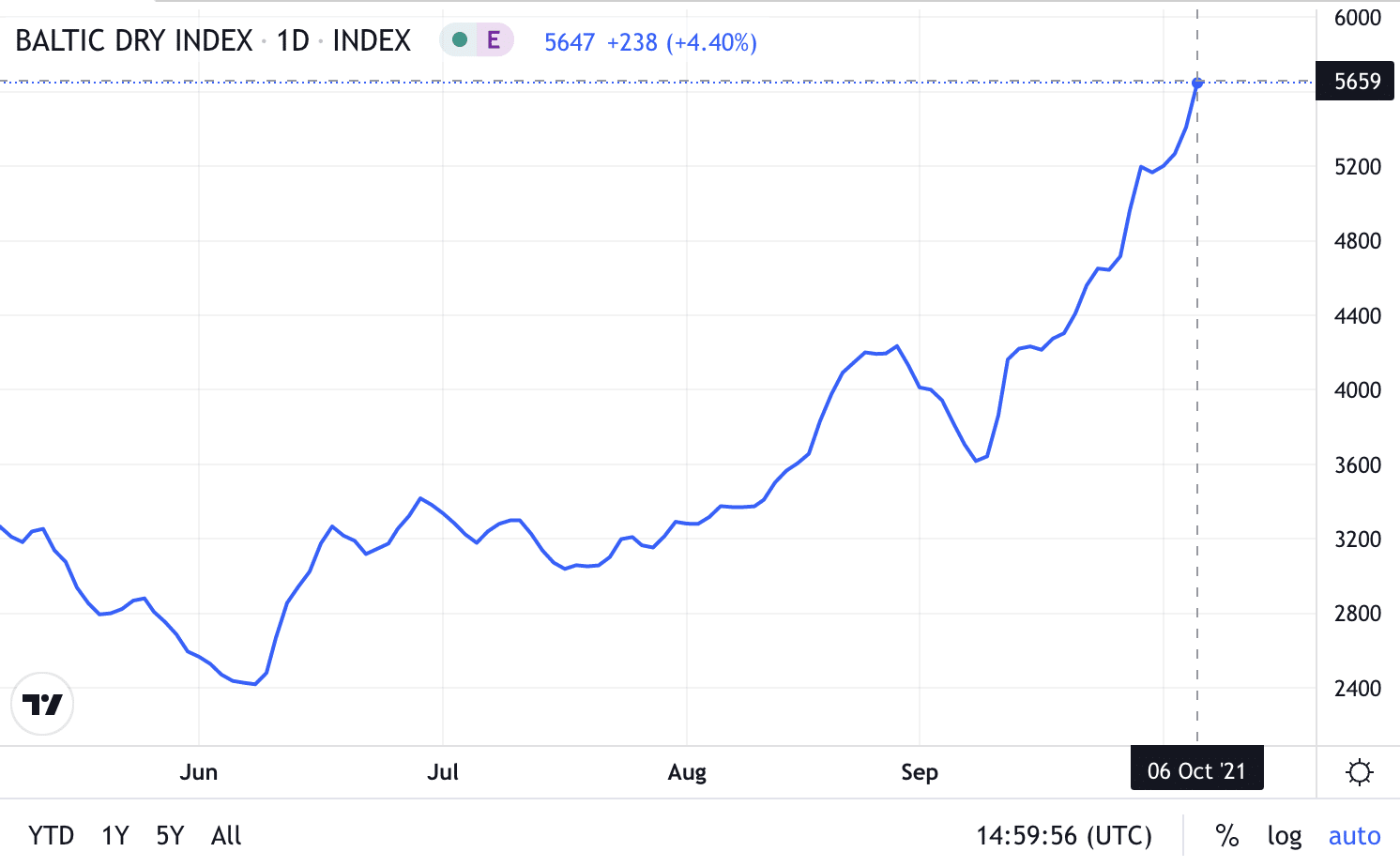

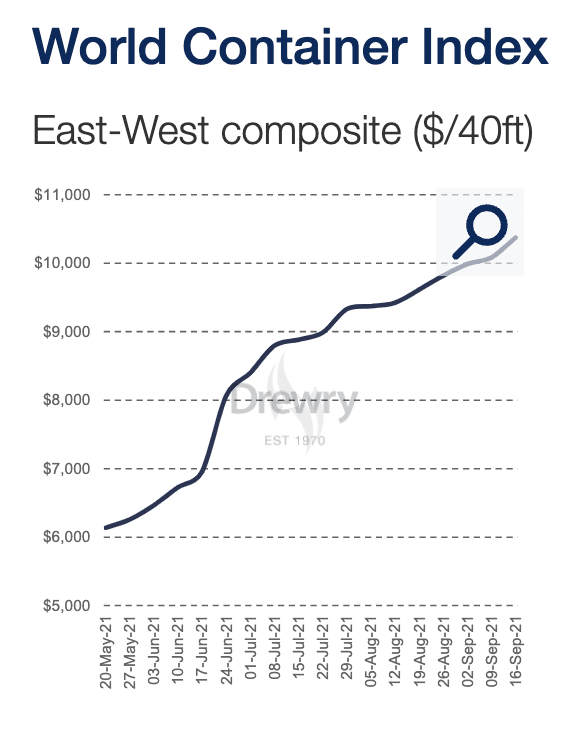

Ocean freight rates have doubled and even tripled over the past year, according to Baltic Dry Index data. Container prices have doubled since May shows data from the Drewry World Container Index.

These jumps in transport costs feed through into how much we pay for our food in the shops, leading to food price inflation.

Producer prices surge will feed through to consumer food prices

Data from the IMF shows that since April 2020 producer food prices rose 47% to May 2021.

Between May 2020 to May 2021, soybean and corn prices jumped a massive 86% and 111%, respectively.

Demand for staples for both people and animals remains elevated, partly because of growing demand in China and stockpiling.

Also droughts we mention earlier are having an effect by reducing harvest yields, so in addition to the US, Brazil and Argentina that we mentioned, we can add Russia and Ukraine.

Then there is demand for biofuels and speculation associated with that. According to Drewry this has led to supply tightness in soybean oil.

Finally some countries are preventing food stuffs being moved out of their country in the name of food security.

Where next for world food prices?

Consumer food price inflation is set to move higher from here, with retailers no longer able to absorb price increases. The IMF expects a pass through of 20% from producer to consumer prices because consumer prices also include things like transport and packaging costs.

The IMF thinks this implies an increase in consumer food price inflation of 3.2% and 1.75% on average worldwide in 2021 and 2022, respectively. A further 1% could be attributed in 2021 to higher freight rates.

But averages hide the variations, and some countries will undoubtedly be hit harder than others.

In the UK there are problems of labour shortages associated with Brexit that is adding to production costs.

For sure, emerging market countries in region such as sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa could struggle the most because of the high proportion of imported food that they rely on.

And more generally, again as previously mentioned, emerging market populations will tend to spend a greater proportion of their income on food, so will be impacted much more from prices rises.

These food price hikes also come at a time when the pandemic has already weakened the ability of households in the less developed countries to cope with more economic shocks.

One last point – a strengthened dollar is bad news for emerging and developing economies as it means paying relatively more for food stuffs that are for the most part traded in US dollars.

All of the above is now combining with energy price inflation to magnify food inflation.

“It’s this combination of things that’s beginning to get very worrying,” said Abdolreza Abbassian, the senior economist at the FAO.