Is China the Missing INF Treaty Ingredient?

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

Russia’s apparent and recent violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force (INF) Treaty suggests it may be time for Russia and the United States to make the Treaty multilateral — and, most importantly, include China.

Russia’s apparent and recent violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force (INF) Treaty suggests it may be time for Russia and the United States to make the Treaty multilateral — and, most importantly, include China.

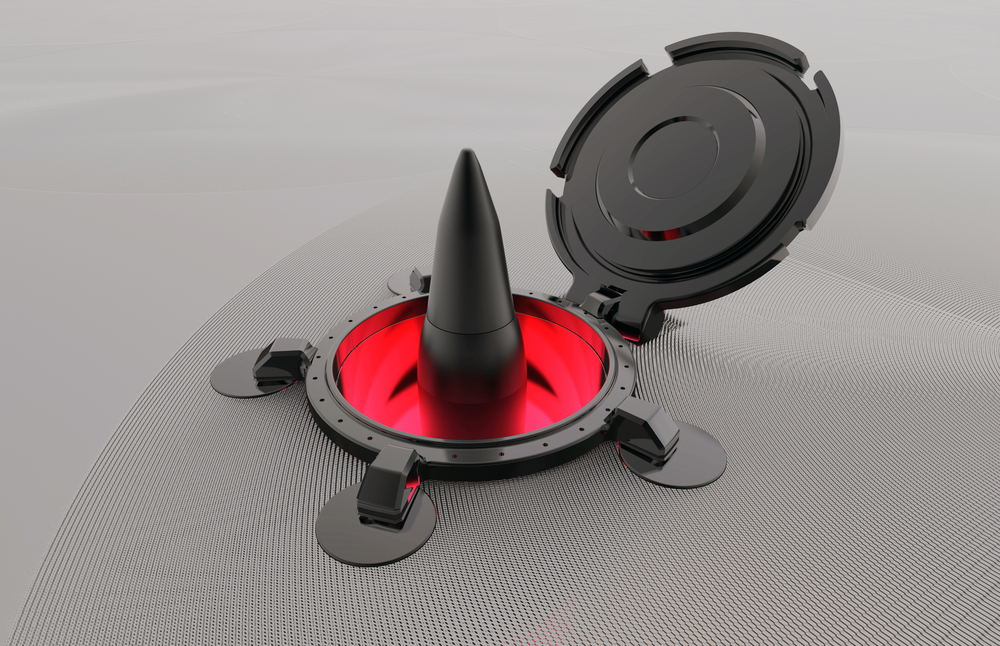

The 1987 INF Treaty was one of the symbols that marked the end of the Cold War. It prohibited the United States and the Soviet Union, later Russia, from producing and deploying land-based ballistic or cruise missiles of intermediate range — between 500 and 5500 kilometres. This was a major success for arms control and marked a significant improvement in the Soviet–American relationship.

The superpowers had agreed to eliminate an entire class of weaponry worldwide and robust verification measures were used to ensure confidence in the Treaty. It was a remarkable achievement. After almost 30 years, the Treaty remains in force, although recent developments have cast a shadow over it.

The darkest cloud is Russia’s apparent violation of the Treaty. In 2015, Russia tested a ground-launched cruise missile that fell within the prohibited range. The Russian violation presents the United States with three options. The United States could ignore the violation in an effort to sustain the relationship with Russia and the Treaty. It could leave the Treaty. Or it could work to meet Russian security concerns by making the Treaty multilateral.

Of these options, making the Treaty multilateral is the best alternative. While all states in possession of land-based missiles in the INF range would be welcome to join, the key actor here is China. This is because it is likely that Russia violated the INF Treaty in part because of its security concerns regarding China.

China’s accession to the Treaty would have a substantial stabilising effect in light of the proliferation of Chinese Intermediate-Range Ballistic missiles and growing Russian concerns. Were China to accede to the Treaty, Russia would still have an incentive to remain within the Treaty, as it bans these missile systems. While that is not a perfect solution, it would allow the Treaty to be saved.

A major objective of arms control is that it can promote stability in relations between states. When a state enters into a treaty arrangement, it signals its acceptance of the status quo. The state willingly limits a class of weapons to demonstrate to other actors that its ambitions are limited and it supports strategic stability.

Joining the INF Treaty allows China to enjoy these benefits of arms control. Were China to sign the Treaty, it would demonstrate its support for stability and acceptance of international norms. China would show that it accepts the value of arms control and seeks confidence-building measures. This would aid stability and demonstrate that China is a status quo power.

More fundamentally, it would also allow China to signal its peaceful intentions. In turn, this could have an important stabilising effect on states concerned with China’s increasing power. Chinese membership in the INF would permit the Treaty to remain in force and address to a considerable degree Russia’s security concerns about China.

This is especially important given China’s tremendous growth in economic and military power and its neighbours’ concerns about China’s aims and objectives now and into the future. Neighbouring states, including not only Russia but also the ASEAN states, India, Japan and Taiwan, will be reassured by China’s acceptance of the INF Treaty. This act would be a major step forward for China and open the door to further arms controls agreements, and the possibility of reducing tensions in East, Southeast and South Asia.

Despite these benefits, there are three major problems from Beijing’s perspective that will generate some resistance to joining the INF Treaty. First, China will have to give up a large number of missiles presently deployed against Taiwan, India and other states. Second, even if China joins, Russia may remain in violation of the Treaty or elect to violate it again in the future. Third, neighbouring states — most notably, Japan, India and Vietnam — would remain outside of the Treaty and would be free to develop their intermediate-range arsenals. Simply put, the Treaty would have both direct costs to China and limit its range of future actions.

Of course, that is precisely the advantage of arms control. The value of demonstrating that China supports the status quo is in China’s long-term national security interests and it will promote stability in international politics. In turn, this will provide China with more security than could be provided by intermediate range forces. Conveying that it is a status quo power, and one that is willing to forsake some of its immediate military advantages in the interests of longer-term security, would dampen the risks of conflict and security competition.

By signing the INF Treaty, China can demonstrate its increasing acceptance of international norms, strategic stability and its intent to be a status quo power. Arms control can play a stabilising role the Sino–Russian–American relationship, just as it did during the Cold War. The potential is there for the future of arms control to effectively contribute to a stable international order founded on binding and transparent strategic agreements rather than nuclear competition.

Why China should join the INF Treaty is republished with permission from East Asia Forum