Here, Let Me Help You Lose that Money

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

In a world where financial experts are frequently proven badly wrong, it is hardly surprising that many people take charge of saving for their retirements themselves. The realities of the financial world do not make this easy, though. In addition, neither does the peculiar psychology of investing – as research in which I have been involved helps to show.

In a world where financial experts are frequently proven badly wrong, it is hardly surprising that many people take charge of saving for their retirements themselves. The realities of the financial world do not make this easy, though. In addition, neither does the peculiar psychology of investing – as research in which I have been involved helps to show.

One common way of saving for the future is investment funds, in which finance professionals pool together the savings of a large number of people and invest them in things like the stock market, bonds and foreign exchange. According to financial theory, the best strategy for choosing a fund is to pick the one with the lowest investment fees and stick with it for as long as possible.

This follows from the efficient-markets hypothesis, which says that financial markets are full of skilled professionals who try to make as much money as possible, so no easy opportunities to make above-average profits remain in the market for long.

Yet in practice, many investors choose funds that have performed well in the past, and chop and change between them – incurring new investment fees each time. The fund industry actively encourages such behaviour by prominently advertising its most successful funds.

Past performance might seem a logical criterion, but research shows it has absolutely no bearing on future performance. On the other hand, the level of investment fees makes a substantial difference. Fees are charged as a percentage of the amount invested, ranging from around 0.05% to about 1.5% a year. These might seem like low amounts, but the differences in compounding can be dramatic.

If you invested US$1,000 in the US stock market in 1970 without paying any investment fees, for example, by the end of 2015 you would have had US$108,968 (a 10.7% average annual return). If you had paid a 1% annual fee, the final investment amount would have been US$71,792 – a reduction of US$37,177.

The regulatory conundrum

The question for regulators is what to do about all the unhelpful marketing. In the UK, for example, there are already rules about how the fund companies can market their funds. All information about past performance has to show the ten-year performance, for instance, which stamped out the old trick of emphasising the performance period over which a fund had had its best run. Other marketing tricks are still legitimate, however, such as putting all the emphasis on your most successful funds while saying less about the laggards.

One option for regulators is to make the fund owners show the data on investment fees and past performance as an actual amount rather than a percentage. Previous research has already shown that large investors are more sensitive to fees if they are a financial amount, and make better investment choices as a result.

What to do about the little guy? Gajus

To develop this we carried out two experiments, each with 1,000 would-be investors. In each experiment, we asked half of the participants to play the part of a large investor and the remainder to play the part of a small investor. The large investors were given hypothetical portfolios of US$1m to invest, while the small investors were each given US$1,000.

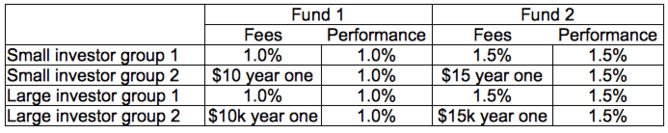

In the first experiment, we asked them all to choose between two funds. One fund had a fee of 1% per annum and a past annual rate of return of 1%, while the other had a 1.5% fee and a 1.5% performance. Instead of giving everyone the information as percentages, half of the small investors and half of the large investors were given the fee information for the first year as a financial charge – US$10/$15 for the small investors, US$10,000/$15,000 for the large investors. In both cases we made clear this was for year one only, and would increase through compound interest in years to come. The rest of the small investors and large investors were given all the data as percentages.

Experiment 1

The results showed that the large investors were more likely to choose a fund based on the fees when the fees were expressed to them as an amount. However, as we had suspected, the small investors did the opposite. They virtually ignored the US$10/$15 charges, believing them to be “peanuts”. It did not matter that the charges were still significant in percentage terms, and would rise in years to come.

In addition, it gets worse …

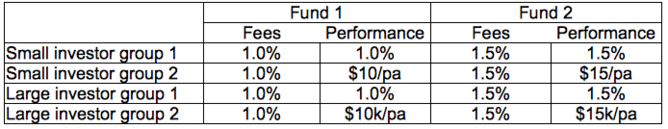

In the second experiment, the investors were given the same two funds to choose from, but this time we varied the way the past-performance data was presented while always listing the fees as percentages. Half the large and small investors were asked to choose between funds whose past performance had been US$10/$10,000 per annum and US$15/$15,000, while the other half were given the performance data as a percentage. The funds had clear disclaimers identical to the ones that appear in real life, saying that past performance makes no difference to future performance.

Experiment 2

The small investors did the same thing in this experiment, but now with a better result: they largely ignored the past returns of US$10 and US$15, and correctly chose the low-fee fund. Translating past returns into small currency amounts helped the small investors to finally ignore what they should have been ignoring in the first place. As a result, in this experiment they outperformed the larger investors overall.

Yesterday’s gone, yesterday’s gone Gunnar Pippel

The conclusion? Large investors and small investors can value the same information differently, which makes it difficult to regulate them all in the same way. Moreover, benefits to different investors vary depending on the variable. In short, one apparently obvious way of improving the marketing information on investment funds may be more trouble than it is worth.

Our experiments give an insight into the difficulties of regulating investment products in a landscape of complex products and ordinary humans. Economists tend to build models that treat us as hyper-rational consumers. If only it were true.

People invest their money illogically – trying to help them can make it worse is republished with permission from The Conversation