Hawley-Smoot-Trump?

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump’s protectionist prescriptions have led to renewed speculation about whether trade wars are on the horizon.

In other words, if, under a Trump presidency, the United States were to raise its tariffs against some of its biggest trading partners – China, Japan, and Mexico – would those countries retaliate in kind? In addition, what would this mean for the global economy?

Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump’s protectionist prescriptions have led to renewed speculation about whether trade wars are on the horizon.

In other words, if, under a Trump presidency, the United States were to raise its tariffs against some of its biggest trading partners – China, Japan, and Mexico – would those countries retaliate in kind? In addition, what would this mean for the global economy?

I had not planned to weigh in on the discussion. That is, not until I came across this brazen assertion by Ian Fletcher – former senior economist of the grassroots Coalition for a Prosperous America – in the Huffington Post:

Trade wars are mythical. They simply do not happen. If you google “the trade war of,” you won’t find any historical examples… History is devoid of them.

Based on his Google test, Fletcher precipitously concludes that trade wars are a myth, a bogeyman concocted by free traders.

I was intrigued by his claims, and, to put it mildly, more than a little skeptical.

As any historical sleuth might do in this situation, I decided to check the sources. I googled “trade war of” and the results were anything but empty.

As a historian of trade, however, I thought it might be even more persuasive to look further into some illuminating examples of trade wars in modern history.

I turned first to the late 19th century, having just written a book on the battle over free trade and protectionism during this period. However, which of the era’s trade wars to examine? After all, there were so many from which to choose. The Romanian-Austro-Hungarian trade war of 1886-93? The Franco-Italian trade war of 1886-95? The era’s Canadian-American trade wars? The Franco-Swiss trade war of 1892-95? The Russo-German trade war of 1893-94? Or perhaps the Spanish-German trade war of 1894-99?

I chose a couple of the more famous cases to illustrate how trade wars are far from mythical.

The Franco-Italian trade war, 1886-95

Soon after Italy’s unification, the young nation turned to infant industrial protectionism, whereupon it terminated its trade agreement with France in 1886.

It raised tariffs as high as 60 percent to protect its industries from French competition. Italy’s turn to protectionism made the French intractable. They refused to negotiate and instead threatened the Italians with punitive tariffs if Italy did not lower its own.

Tariff retaliation followed tariff retaliation. In France, this resulted in the passage of the highly protectionist Méline Tariff of 1892, which famously signaled the death knell of the country’s flirtation with free trade.

Both nations felt the costs of the trade war. Franco-Italian trade fell drastically, followed by dislocations in their supply sources and markets. Another unintended result was that it pushed Italy closer to Germany and Austria-Hungary in the years leading up to the First World War.

Canadian-American trade wars, circa 1866-97

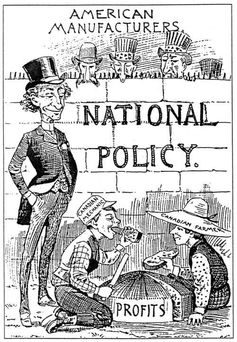

This cartoon lampoons how U.S. protectionism hurts American companies. The Industrial League for Free Distribution

Immediately after the Civil War, the United States abrogated its reciprocity treaty with Canada, following which Canadian economic nationalists sought to pay their southern neighbor back “in their own coin” – that is, through tariff retaliation.

By 1879, Canadian Conservatives consolidated around their National Policy of protectionism. Some American companies – Singer Manufacturing, American Tobacco, Westinghouse and International Harvester – decided to move their production to Canada rather than pay the high import taxes. By the late 1880s, 65 U.S. manufacturing plants had relocated to Canada. In this case, far from halting outsourcing, protectionism caused it.

Trade tensions reached a breaking point in 1890. Republicans, controlling the executive and the legislative branches, passed the highly protectionist McKinley Tariff. Tariff retaliation was, according to Sir Alexander Galt – the first Canadian high commissioner in London – “the only argument applicable in the present case.” Canadian agricultural exports fell by half from 1889 to 1892.

In addition, when the Republicans passed the even more protectionist Dingley Tariff in 1897, Canada decided that the best response was a double dose of tariff retaliation and closer trade ties with the British Empire rather than the United States. It took nearly a century after this for free trade between the U.S. and Canada to develop.

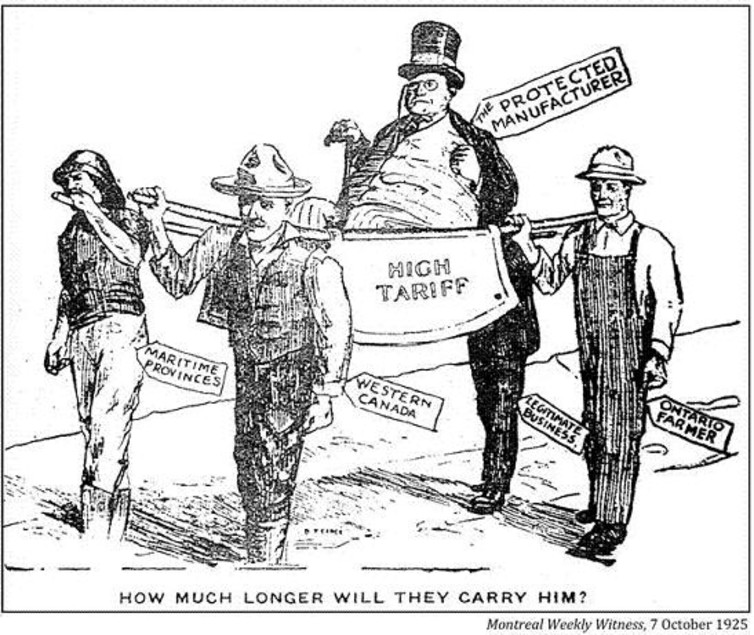

The fight between free traders and protectionists has been going on for a long time. Montreal Weekly Witness

The trade wars of the Hawley-Smoot Tariff of 1930

Trade wars were by no means unique to the late 19th century. Far from it.

The trade wars that followed the Republican passage of the protectionist 1930 Hawley-Smoot Tariff are particularly illustrative, with lessons for today. For example, Canada responded with tariff increases of its own, as did Europe. In a widely cited study from 1934, Joseph M. Jones Jr.’s “Tariff Retaliation: Repercussions of the Hawley-Smoot Bill” explored Europe’s retaliation. His study provided a warning about the trade wars that can arise:

when an autonomously determined tariff in the United States can threaten with ruin these specialized industries in foreign countries, when it can arouse the population of Switzerland through an increased duty on watches, when it can arouse the French nation through a proposed increase in the duty on a particular kind of lace, when it can arouse bitterness throughout Spain by an increased duty on cork, throughout Italy by an increased duty on olive oil, throughout Canada by increased duties upon a negligible flow of borderline traffic in foodstuffs and raw products.

To provide but one example from Jones’ study, the Italian public responded violently to the Hawley-Smoot Tariff. American-made cars were attacked and befouled on the streets of Italy. In addition, in June 1930, Mussolini vowed, “Italy will defend herself in her own way.” Tariff duties were increased on U.S. goods, causing exports to Italy to plunge from US$211,000,000 in 1928 to $58,000,000 in 1932.

More broadly, Douglas Irwin notes how the 1930 U.S. tariff “was very damaging from the standpoint of U.S. commerce” because it sparked tit-for-tat trade discrimination against the United States and “diverted existing trade away from the United States.”

Paul Krugman has similarly reminded us that, although the Hawley-Smoot Tariff did not cause the Great Depression, the resulting international trade wars played a critical part “in preventing a recovery in trade when production recovered.”

Far from fantasy

I will leave it to others to debate whether or not trade wars with America’s largest trading partners would be a net positive or negative for the United States.

But what I do hope comes across is that, even with a little bit of Google searching, myriad historical examples of trade wars can be found. To suggest that trade wars are a historical myth is just plain fantasy.

Do protectionist policies like Trump’s lead to trade wars? is republished with permission from The Conversation