Greece Exit (GREXIT) – A Boon or a Bane?

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

Greece joined the Eurozone as its 12th member in 2001 but was the first to be bailed out in 2010 ever since the Eurozone crisis in 2009. After government borrowing rates soared, Greece secured another bailout in 2010 of $142 billion following a second package earlier in 2012. Both were in return for promises of tough austerity cuts. By the end of 2014, Greece owed “troika”(European Central Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission) €253.3bn. In 2014, many talks were doing the rounds of a possible exit of Greece from the Eurozone.

Greece joined the Eurozone as its 12th member in 2001 but was the first to be bailed out in 2010 ever since the Eurozone crisis in 2009. After government borrowing rates soared, Greece secured another bailout in 2010 of $142 billion following a second package earlier in 2012. Both were in return for promises of tough austerity cuts. By the end of 2014, Greece owed “troika”(European Central Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission) €253.3bn. In 2014, many talks were doing the rounds of a possible exit of Greece from the Eurozone.

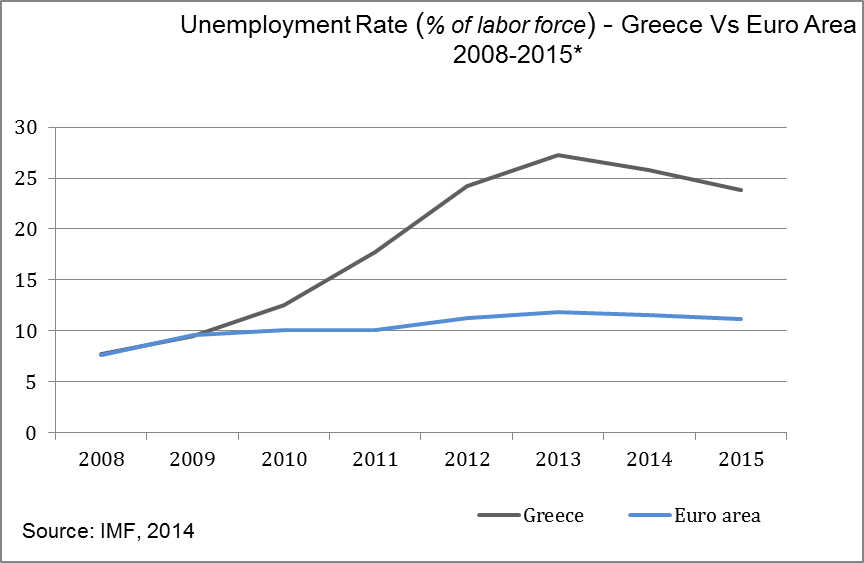

According to a report (2015) by Gallup (Phoebe Dong and Chris Rieser), 18% of the Greek population approved of their country’s leadership in 2014. With snap elections in January 2015, Greece is again put on a spot. There is a lot of speculation as to how things could change for Greece in case radical left-wing party Syriza wins. The party’s leader, Alexis Tsipras looks set to become prime minister of the troubled nation that witnesses an unemployment rate of 26%, according to The Economist. The Greek economy looks 25% smaller than it was before the crisis. With high unemployment rate, even those employed get low wages and if someone is without a job for more than a year, then they lose their social security. Around 60% of Greek population (under 25) remains unemployed.

The Debt Story of Greece

Last week Greece saw two of its four main banks seek access to emergency funds from the European Central Bank (ECB). Emergency liquidity assistance is when banks run out of assets used as collateral for borrowing at favorable rates from ECB and Greek banks had already received such assistance in 2012.

Greece government debt crisis is also termed as the Greek Depression started with the downgrading of the Greek government debt to junk status by Credit Rating Agencies in 2010. In the same year, IMF and Eurozone countries agreed on first bailout of €110-billion bailout loan, which came with conditions: Implementation of austerity measures to restore the fiscal balance, privatization of government assets worth €50bn by the end of 2015 (to keep the debt pile sustainable) and implementation of outlined structural reforms so as to improve competitiveness and growth prospects.

The net debt of Greece was around 130% of GDP in 2010 according to the IMF and is now close to 175%. The economy has shrunk so the debt ratio has increased and it’s put the country described as the “debt trap”. But many have raised concerns about the level of net debt Greece faces. According to Forbes, Germany has been overvaluing Greece’s debt by failing to follow the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (Ipsas), which measure liabilities and assets over time. Going by Ipsas calculations, Greece faces a net debt of 18% of GDP and not 175%. One of the biggest reasons for not using Ipsas for calculation of Greek Debt is cited in the article (Greece’s Net Debt Is 18% of GDP, Not 175%. What’s Germany’s?) is that overestimating sovereign debt for Southern European countries could stir anxiety in foreign currency markets, depressing the Euro, and firing up Germany’s export engine. Many economists believe that reducing the debt burden in Greece could help Greek economy and could also prove helpful for the entire Eurozone.

Nothing will be the same for Greece after Monday

Sunday Elections for Greece could either make or break the future of Greece depending how the elected government handles rising tensions between the troubled nation and its creditors, Eurozone government and IMF. So far, Greece has been receiving bailouts and trying hard to remain in the Eurozone. The next Greek Government could reach some important decisions regarding Greece’s bailout program. Syriza is very likely to win but as elections come close, political uncertainty looms over the country. The rising political uncertainty also caused the Troika to hold all planned remaining financial aid to Greece under its bailout programme. The support would only continue after the formation of a new-elect government that will be respecting the already negotiated conditions. Analysts and economists stand opinionated regarding the decisions by the next elected government.

Many analysts are of the opinion that if elected, Syriza could negotiate debt relief deal with Troika – the European Commission, European Central Bank (ECB) and IMF. Negotiations could include forgiveness of a part of Greece’s debt and/or acceptance of deal on fiscal discipline or a mutually beneficial deal. However, these negotiations will be a bit tough, if Syriza gets in power, since it rejects the privatization and deregulation measures suggested by its creditors and Germany. These measure are considered to be essential for the revival of Greece’s economy but this could be debatable between the government and its creditors. Both Tsipras and German Chancellor Angela Merkel want Greece to be a part of Eurozone. Both Greece and Germany have more interest in striking a deal than allowing Greek to default. The Guardian explains that as the election gets closer Tsipras is ‘moderating’ his talks.

Even though there is a likelihood of Greece arriving at a negotiable to restructure its debt, IMF’s Managing Director Christine Lagarde thinks otherwise. She told The Irish Times in an interview on 19th January 2015 “As a principle, collective endeavors are welcome but at the same time a debt is a debt and it is a contract.” In case there is no conclusive negotiation, Greece exit (Grexit) from Eurozone could be possible. If Greece does chose to exit, then it will be the first to leave the common currency union. It could also mean that other weaker countries like Portugal, Italy and Spain may follow next breaking Eurozone’s foundation.

But what happens to Greece if it is not a part of the common currency?

Abandoning the Euro would mean that Greece would get back to its former currency, the drachma, which could be disastrous, especially when the economy is failing and its debt unsustainable. The decision could lead to heavy deposit withdrawals from Greek banks leading to capital flight from the country. However, many analysts disagree and suggest that leaving Eurozone could work well for Greece since it would have greater control over its economic situation and restore competitiveness.

The European Central Bank (ECB) announced its programme of Quantitative Easing a few days before Greek elections to be held on 25th January 2015. Quantitative helps create money, whereby typical purchases of government and corporate bonds are made. As the demand increases, the price also rises allowing the yield to fall. It helps improve the liquidity position of banks making more money available to them for lending to businesses and consumers. It plans to spend $70 billion a month for at least 19 months, adding substantial purchases of government bonds to an existing scheme to buy covered bonds and asset-backed securities. Special rules have been laid down for Greece, which has already received bailouts. If Greece decides to exit (under non-negotiable terms), then it will default on its debt. ECB has set rules that in such a case, there would be no purchases of Greek Bonds in the immediate future. Also there will be a limit of 33% on the amount of a country’s bonds that can be purchased.

Greece faces extreme financial hardships and corruption making it worse for its own people. The borrowed money has only helped a single section – Greek Banks while the people continue to face unemployment, low wages and low pensions. With 18% of the country’s population not meeting food needs, 32% still remain below poverty line and have no national health insurance. Amidst all this, a new government in Greece could bring new hope and likelihood of a fresh start to the country. As John Humphrys puts it “Whatever the future may hold for them, it can’t be worse than what has happened in the past.”

Greece Exit (GREXIT) – A Boon or a Bane? is republished with permission from The Financial Keyhole

.png)