Global High-Tech Supply Chain Shaken by Japan Crisis

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

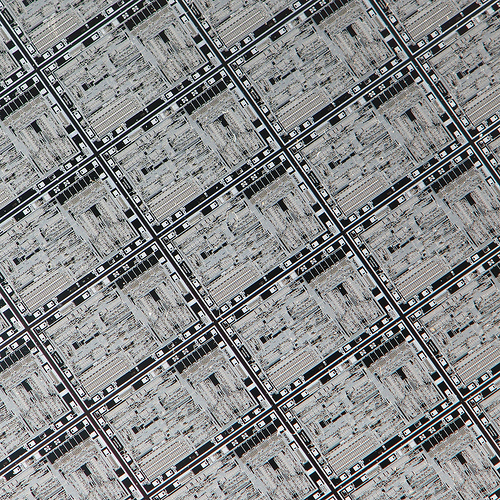

Silicon Wafers:

Crucial Link in Global Hi-Tech Supply Chain

Credit: pengo-au

23 March 2011.

Silicon Wafers:

Crucial Link in Global Hi-Tech Supply Chain

Credit: pengo-au

23 March 2011.

Yesterday, we looked at the impact of the Japan crisis on the world auto industry.

Today, we examine its effect on the equally sensitive supply chain in global high-technology.

Tony Prophet, a senior vice president for operations at Hewlett-Packard, was awakened at 3:30 a.m. in California,

and told that an earthquake and tsunami had struck Japan.

Soon after, Prophet had set up a virtual “situation room,” so managers in Japan, Taiwan and America could instantly share information.

Prophet oversees all hardware purchasing for H.P.’s $65-billion-a-year global supply chain, which feeds its huge manufacturing engine.

The company’s factories churn out two personal computers a second, two printers a second and one data-center computer every 15 seconds.

While other H.P. staff members checked on the company’s workers in Japan — none of whom were injured in the disaster —

Prophet and his team scrambled to define the impact on the company’s suppliers in Japan and, if necessary, to draft backup plans.

“It’s too early to tell, and we’re not going to pretend to predict the outcome,” Prophet said in an interview last week. “It’s like being in an emergency room, doing triage.”

The emergency-room image speaks volumes.

Modern global supply chains, experts say, mirror complex biological systems like the human body in many ways.

They can be remarkably resilient and self-healing,

yet at times quite vulnerable to some specific, seemingly small weakness —

as if a tiny tear in a crucial artery were to cause someone to suffer heart failure.

Day in and day out, the global flow of goods routinely adapts to all kinds of glitches and setbacks.

A supply breakdown in one factory in one country, for example, is quickly replaced by added shipments from suppliers elsewhere in the network.

Sometimes, the problems span whole regions and require emergency action for days or weeks.

But the disaster in Japan, experts say, presents a first-of-its-kind challenge, even if much remains uncertain.

Japan is the world’s third-largest economy, and a vital supplier of parts and equipment for major industries like computers, electronics and automobiles.

The worst of the damage was northeast of Tokyo, near the quake’s epicenter,

though Japan’s manufacturing heartland is farther south.

But greater problems will emerge if rolling electrical blackouts and transportation disruptions across the country continue for long.

Throughout Japan, many plants are closed at least for days, with restart dates uncertain.

More made-in-Japan supply-chain travails are expected.

“This is going to be a huge test of global supply chains, but I don’t think it will be a mortal blow,” says Kevin O’Marah, an analyst at Gartner-AMR Research.

“I think that over all we’ll see how resilient and quick-learning these networks have become.”

The good news for the world’s manufacturing economy is that the sectors where Japan plays a vital role are fairly mature, global industries.

Consider computing and electronics.

For major components, like semiconductors, production is now spread across several countries.

By contrast, in the early 1990s, virtually all 486-microprocessors —

the engines of the most powerful personal computers of the time —

were made at a single Intel factory near Jerusalem.

Japan’s importance in the semiconductor industry as a whole has receded in recent years,

as more production has shifted to South Korea, Taiwan and even China.

Japan accounts for less than 21 percent of total semiconductor production,

down from 28 percent in 2001, according to IHS iSuppli, a research firm.

Still, Japan produces a far higher share of certain important chips

like the lightweight flash memory used in smartphones and tablet computers.

Japan makes about 35 percent of those memory chips, IHS iSuppli estimates, and Toshiba is the major Japanese producer.

But South Korean companies, led by Samsung, are also large producers of flash memory.

Apple, like all major companies these days, treats its supply-chain operations as a trade secret.

But industry analysts estimate that Apple buys perhaps a third of its flash memory from Toshiba, with the rest coming mainly from South Korea.

The lead time between chip orders and delivery is two months or more.

A leading customer like Apple will be first in line for supplies, and it has inventories for several weeks, analysts say.

So there will be little immediate impact on Apple or its customers,

but even Apple will likely be hit with supply shortages of crucial components in the second quarter,

predicts Gene Munster, an analyst at Piper Jaffray.

The field of buying and shipping supplies has been transformed in the last decade or two.

Globalization and technology have been the driving forces.

Manufacturing is outsourced around the world, with each component made in locations chosen for expertise and low costs.

So today’s computer or smartphone is, literally, a United Nations assembly of parts.

That means supply lines are longer and far more complex than in the past.

The ability to manage these complex networks, experts say, has become possible because of technology —

Internet communications, RFID tags and sensors attached to valued parts, and sophisticated software for tracking and orchestrating the flow of goods worldwide.

That geographic and technological evolution, in theory, should make adapting to the disaster in Japan easier for corporate supply chains.

“In the past, when you had a disruption, the response was regional,” says Timothy Carroll, vice president for global operations at I.B.M.

“Now, it’s globalized.”

Most anything can be tracked, but it takes smart technology, investment and effort to do so.

And as procurement networks become more complex and supply lines grow longer —

“thin strands,” as the experts call the phenomenon —

the difficulty and expense of seeing deeper into the supply chain increases.

“Major companies have constant communications and deep knowledge of primary suppliers,”

says David Yoffie, professor at Harvard Business School.

“It’s in the secondary layers of suppliers — things that are smaller, barely noticed — where the greater risk is.”

Indeed, supplies of larger, more costly electronic components, like flash memory and liquid crystal displays, tend to grab the most attention.

But, says Tony Fadell, a former senior Apple executive who led the iPod and iPhone design teams,

“there are all kinds of little specialized parts without second sources, like connectors, speakers, microphones, batteries

and sensors that don’t get the love they deserve.

Many are from Japan.”

Lacking some part, even if it costs just dimes or a few dollars, can mean shutting down a factory, Mr. Fadell adds.

A recent analysis by IHS iSuppli, taking apart a new Apple iPad2, identified five parts coming from Japanese suppliers:

• flash memory from Toshiba,

• random-access memory for temporary storage from Elpida Memory,

• an electronic compass from AKM Semiconductor,

• touch-screen glass from Asahi Glass, and

• a battery from Apple Japan.

Further down the supply chain lie raw materials.

Trouble for a supplier to a company’s parts supplier can cascade across an industry.

For example, reports that a Mitsubishi Gas Chemical factory in Fukushima was damaged by the tsunami

have fanned fears of a coming shortage of a resin — bismaleimide triazine, BT —

used in the packaging for small computer chips in cellphones and other products.

Two Japanese companies are the leading producers of silicon wafers, the raw material used to make computer chips,

accounting for more than 60 percent of the world’s supply.

The largest is the Shin-Etsu Chemical Corporation.

Its main wafer plant in Shirakawa was damaged by the earthquake, and the factory is down.

“The continuing violent aftershocks are complicating the inspection work,” said Hideki Aihara, a Shin-Etsu spokesman in Japan, on Friday.

“Right now we can’t say how badly it was damaged or how long it might take to get started.”

Shin-Etsu does have factories outside Japan.

“But the most advanced manufacturing and silicon-growing processes are done in Japan,” says Klaus Rinnen, a semiconductor analyst at Gartner.

And growing silicon ingots, which are then sliced into wafers, is a lengthy, delicate process

that will be hampered by power failures or other disruptions, he says.

Big chip makers like Intel, Samsung and Toshiba typically hold inventories of silicon wafers for four to six weeks of production.

“But after that, it will get tougher,” Mr. Rinnen says.

The Japan quake, some experts say, will prompt companies to re-evaluate risk in their supply chains.

Perhaps, they say, there will be a shift from focusing on reducing inventories and costs, the just-in-time model, pioneered in Japan,

to one that places greater emphasis on buffering risk — a just-in-case mentality.

Adding inventories and backup suppliers reduces risk by increasing the redundancy in a supply system.

It is one way to enhance resilience, experts say, but there are others.

They point to an example that is well known to supply-chain mavens.

In 1997, there was a fire at a plant of one of Toyota’s main suppliers, Aisin Seiki, which made a brake valve used in all Toyota vehicles.

Because of the carmaker’s just-in-time system, the company had just two or three days of stock on hand.

So the fire threatened to halt Toyota’s production for weeks.

But Toyota and teams of suppliers in the company’s supply-chain network worked round the clock for days to design and set up alternative production sites.

Toyota’s assembly plants reopened after being shut down for just two days, says the New York Times.

“That kind of resilient capability, I think, is what we’ll see in Japan over the weeks and months ahead to put these supply chains back on their feet,”

says Charles H. Fine, a professor at the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For global operations managers like Prophet of H.P., the Japanese disaster will be a severe test of their supply networks and systems.

We’ll see what happens.

David Caploe PhD

EconomyWatch.com