Fallout of a Slowing China on Emerging Asian Economies

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

With its rapid economic growth and integration into the global economy over the last 3 decades, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has emerged as a major economic power and an important source of growth for the world economy. Now it is the second-largest economy at market exchange rates and the largest exporter in the world.

With its rapid economic growth and integration into the global economy over the last 3 decades, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has emerged as a major economic power and an important source of growth for the world economy. Now it is the second-largest economy at market exchange rates and the largest exporter in the world.

In Asia, the PRC’s role as a growth pole is even more prominent. Over the last 10 years, spurred by strong processing exports and domestic demand, the PRC’s imports from Asia in US dollar terms have increased at an average annual rate of 9%. Strong demand from the PRC also supported prices of commodities exported by Asian and other emerging economies.

The increasing importance of the PRC for other Asian economies represents not only opportunities for them, but also a potential source of macroeconomic risk. With increased integration in the regional economy, a slowdown in the PRC’s economy is likely to spill over to elsewhere in Asia. After peaking at 10.6% in 2010, the PRC’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth has decelerated sharply since then, dropping to below 7% in 2015.

With its traditional growth drivers—exports and investment—losing their momentum, the PRC’s current growth model may have reached its limits. The PRC National People’s Congress has just approved a new growth target of 6.5%–7% for the next 5 years; still strong growth, but markedly slower than the earlier trend. Moreover, the risk of a hard landing remains. Therefore, it is important to identify the risks for the rest of Asia.

Methodology

Our recent study (Zhai and Morgan 2016) assesses the likely implications of a growth slowdown in the PRC for emerging Asian economies. Specifically, we use a multi-sectoral computable general equilibrium (CGE) model of the global economy to investigate the macroeconomic and structural impacts of the PRC’s slowdown through the trade channel.

The CGE model is an economy-wide model that characterizes interactions among industries, consumers, and governments across the global economy. The detailed regional (20 economies and regions) and sector disaggregation (22 sectors) of the model makes it possible to capture the spillover effects of economy- or sector-specific shocks.

In the model, domestic investment is exogenously set to reflect a shock in investment demand. As government savings are exogenous and foreign savings are determined by the foreign account balance, the investment–savings account has to be balanced through the changes in the levels of household saving.

The equilibrium is achieved through an endogenously adjusted economy-wide factor capacity utilization rate for both capital and labor, which in turn results in changes in household income and savings.

We first establish a baseline forecast, in which economic growth and other macroeconomic indicators are broadly assumed consistent with the projections of the International Monetary Fund’s recent World Economic Outlook (IMF 2015). In the baseline, the PRC is assumed to achieve a GDP growth rate of 6.2% in 2016–2020.

Then, we consider the counterfactual scenario a cut in the PRC’s real investment growth by 3 percentage points during 2016–2020. This translates into a GDP growth slowdown of 1.6% for the PRC, or only 4.6%.

Findings

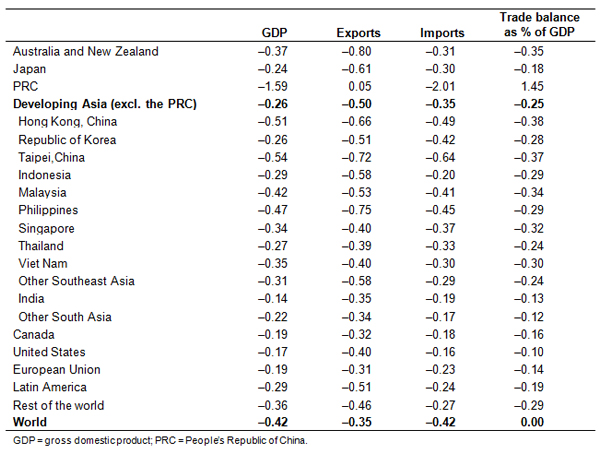

Our model-based analysis suggests that its adverse impacts on regional economies would be relatively modest. The table below summarizes the impacts on GDP, exports, imports, and the trade balance of major regions and economies.

A growth slowdown of 1.6 percentage points in the PRC would bring about a growth deceleration of 0.26 percentage points in developing Asia as a whole (excluding the PRC). In most regional economies, the induced growth losses are less than 0.5 percentage points. Taipei, China and Hong Kong, China are most vulnerable to the PRC’s economic downturn, while South Asia is the most isolated from changes in the PRC.

Effects of the PRC’s Slowdown on GDP and Trade, 2016–2020

(percentage point changes in annual growth rates relative to the baseline, except for trade balance)

Source: Authors’ model simulations

Although the simulation results lie in the range of other alternative estimations in literature, several important limitations in this modeling exercise need to be mentioned.

First, the modeling analysis captures the trade channel of international business cycle linkage only. It does not include some of the other transmission channels, such as private capital flows, contagion in regional financial markets, and services trade in tourism.

Second, the model lacks financial variables and nominal prices changes. This absence limits its ability to incorporate macroeconomic adjustment behaviors and policies that are important to determine the transmission of macroeconomic fluctuations.

For instance, the model assumes bilateral real exchange rates are constant throughout the simulations. This may lead to underestimation of the spillover effect of the PRC’s slowdown as economies experiencing a negative demand shock often face pressure of real depreciation.

Third, the model is still highly aggregated and it may underestimate the impact of a slowdown of the PRC’s investment growth in some special commodity markets. Fourth, as vertical specialization and the fragmentation of productive processes (supply chain networks) are not explicitly modeled in the CGE framework, the simulation results may overestimate the effect of demand shock originating from the PRC.

Therefore, the results reported in our paper (Zhai and Morgan 2016) should be viewed as indicative rather than forecasts.

Policy implications

Two major policy implications emerge from the above analysis.

First, most Asian economies have relied on exports as the major source of growth. This has rendered their economies vulnerable to the business cycles of either the developed markets or the PRC.

To maintain a stable macroeconomic environment and enhance economic flexibility is important to mitigate the external shocks. A switch of development strategy from export-led growth to domestic demand-led growth would also be more important than before for Asian economies to achieve sustainable growth.

Second, the PRC will play an even larger role in the world economy and provide a strong support for the regional demand growth in the future. Stronger growth in the PRC’s domestic economy, together with increasing links through regional production chains and outward direct investment, would make Asian developing economies more exposed to economic fluctuations in the PRC and lead to higher business cycle synchronization in regional economies.

This would call for Asian economies to strengthen coordination of macroeconomic policies.

Impact of a possible growth slowdown of the People’s Republic of China on emerging Asia: a general equilibrium analysis is republished with permission from Asia Pathways