Do Bowie Bonds Have a Future?

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

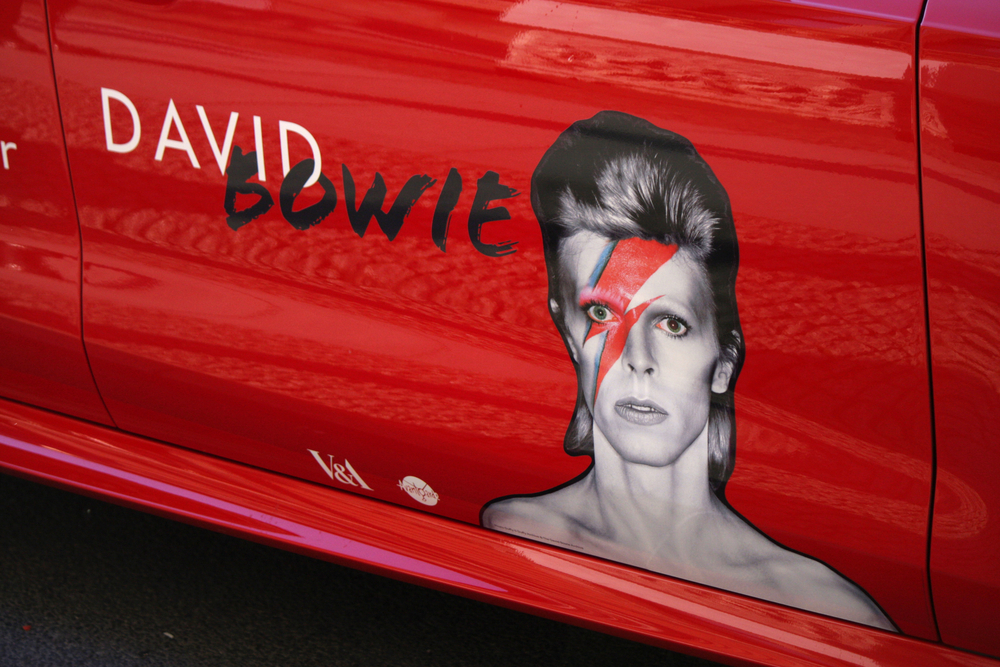

The recent death of David Bowie brought an enormous wave of eulogies focused on his revolutionary career in rock music. Many of the laudatory discussions concerning Bowie’s countless musical and performance innovations mentioned his trailblazing contribution to the world of finance: the asset-backed securities known as “Bowie Bonds”.

How They Began

There are nearly as many explanations for the 1997 genesis of Bowie Bonds as the number of articles dealing with the subject. Some claim that Bowie foresaw the impending hardship for the music industry, resulting from the advent of digital recording and “streaming”. Many of these discussions focused on the singer’s 2002 interview with Jon Pareles of The New York Times, which included this prophecy:

“I’m fully confident that copyright, for instance, will no longer exist in 10 years, and authorship and intellectual property is in for such a bashing.”

Bowie’s prediction actually extended to the entire area of intellectual property rights, beyond those impacted by digital recording. In fact, this idea has its roots in the assertions by Marshall McLuhan, who wrote in the spring, 1966 issue of the American Scholar:

“Xerography is bringing a reign of terror into the world of publishing because it means that every reader can become both author and publisher.”

Despite Bowie’s prescient notion that copyright protection would become a major challenge for the music industry, the most logical explanation for his 1997 decision to issue bonds was that he simply needed money.

The Project Begins

Tom Espiner of BBC News reported that in the 1970s David Bowie first learned that he did not own all of the rights to his music catalog. Tony DeFries, who had been Bowie’s manager until 1975, owned 50% of the rights to the music Bowie created up to an unspecified point in time.

Bowie was eventually able to purchase the rights held by DeFries for an estimated $27 million. In the mid-1990s, Bowie’s financial manager, Bill Zysblat, put the artist in touch with investment banker David Pullman, who was working for Gruntal & Co. at the time. Pullman was working forFahnestock & Co. when the bond offering finally came in 1997.

With the help of Bill Zysblat, Bowie entered into a licensing agreement with record label, EMI. The deal gave Bowie the right to securitize the royalties for 25 albums released between 1969 and 1990.

The royalty stream backed the issue of $55 million in $1,000 bonds, underwritten by Fahnestock & Co. The bonds paid 7.9% interest for ten years, after which point 100% of the royalties would be payable to David Bowie. Prudential Insurance Company of America purchased the entire bond issue.

After founding Pullman Group, L.L.C., David Pullman created similar bonds for Ashford & Simpson, James Brown, the Isley Brothers, and Marvin Gaye. Pullman eventually used the term “Pullman Bond” to describe these securities. At the Pullman Group website, a diagram illustrates the entertainment-asset securitization process for Pullman Bonds.

Battle Royale

In a November 20, 2000 article for The Observer, Landon Thomas described the feud which eventually arose between David Pullman and David Bowie’s financial manager, Bill Zysblat. Zysblat began competing with Pullman immediately after the Bowie deal, at which point both Zysblat and Pullman believed that the music royalty market could be worth as much as $1 billion.

By 2000, Zysblat concluded that the music royalty market was worth no more than $100 million, with rising interest rates making the situation even less lucrative. On the other hand, the Observer article highlighted Pullman’s boast that he had booked $105 million in deals since the Bowie offering. The article also pointed out that in September of 1999, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office refused to issue a trademark for Pullman’s use the name “Bowie Bonds”.

After selling the Bowie Bonds to Prudential, Bill Zysblat, acting as principal for Rascoff/Zysblat Organization, Inc. (RZO), entered into a joint venture, whereby Prudential and RZO would jointly engage in creating securities backed by future entertainment royalties. As a result, in November of 1999, Pullman Group L.L.C. filed suit against Prudential, RZO, a law firm, which advised Fahnestock on these matters and several other defendants.

Pullman Group’s lawsuit asserted 25 separate causes of action alleging misappropriation of trade secrets, intellectual property and innovative expertise. In August of 2000, Judge Beatrice Shainswit of the New York State Supreme Court (the trial level court in the state of New York) granted Defendants’ motion to dismiss the suit on the basis that the Pullman Group’s founding came in 1998, after the 1997 consummation of the Bowie deal.

Pullman Group therefore lacked standing to sue. The dismissal was affirmed by the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of the State of New York on November 1, 2001, as reported in Pullman Group, L. L. C. v. Prudential Insurance Company Of America et al., 733 N.Y.S.2d 1 (First Department, 2001).

Conclusion

The novelty of Bowie bonds has been exaggerated in many instances. A January 12, 2009 article by Evan Davis for the Daily Mirror asserted that Bowie bonds “may have started the credit crunch.”

That theory ignores the fact that mortgage-backed securities have been in existence since the 1970s. On a more sober note, a recent article in Billboard explained that Bowie bonds were an outgrowth of the type of “off balance sheet” funding provided to production studios by firms such as Silver Screen Partners in the 1980s.

A January 11, 2016 report in The Wall Street Journal disclosed attempts by both Royal Bank of Scotland and Nomura to create bonds based on bundled future income streams from a group of artists. These plans never materialized because the stream of cash flows necessary to back bonds required a significant body of work, beyond what the artists involved created.

It remains doubtful that securitization of royalties will continue in the music industry because royalty rates and sales of recorded music are shrinking. On the other hand, The Wall Street Journal noted that Fantex Holdings has begun issuing securities tied to the earnings of professional athletes.

Will the flow of publicity about Bowie bonds since the artist’s death have the ironic impact of breathing new life into the use of securities based on royalty streams? Time will tell.