Cost of the Iraq War: Iraq has the ‘Worst of All Worlds’

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

6 December 2010. It is true that the Iraq War has already cost more on a per-capita basis than the Marshall Plan, which re-built post-war Japan and Germany as thriving economies. But the real cost of the war is that the Iraqi people have been left with the worst of both worlds.

6 December 2010. It is true that the Iraq War has already cost more on a per-capita basis than the Marshall Plan, which re-built post-war Japan and Germany as thriving economies. But the real cost of the war is that the Iraqi people have been left with the worst of both worlds.

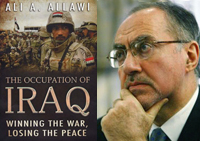

This is an interview with Ali Allawi, the first civilian minister of defence in Post Saddam Iraq. Allawi studied in MIT, LSE and Harvard University before becoming a merchant banker and holding visiting posts in a number of academic institutions, including the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at Oxford University. During the 1980s and the 1990s, Allawi was a prominent member of the London-based Iraqi opposition to Saddam Hussein’s regime.

Allawi returned to Iraq in September 2003 and became a minister of trade, then defense, and finally finance. He left the government in 2006.

Author of the book The Occupation of Iraq: Winning the War, Losing the Peace Allawi is currently a senior visiting fellow at the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. This story first appeared in the e Middle East Quarterly in its autumn 2010 edition. We print an abridged edition here.

A Justified War?

Middle East Quarterly: With the benefit of hindsight, was the 2003 Iraq war justified?

Ali Allawi: The answer, I am afraid, is equivocal. It depends on what term you use to justify the invasion. If you launch a war that is driven by mainly moral or ethical considerations with a specific purpose of removing a terrible dictatorship and replacing it with something else, then yes, you can make a case for that. But the war was never claimed to be a just war. It was waged in order to uncover weapons of mass destruction [WMD], so it’s like a post factum justification. On balance, the answer is yes—we removed the dictatorship; no—because the mismanagement and subsequent disaster that befell the country could have been and should have been avoided and, therefore, perhaps overshadowed the removal of the dictatorship.

MEQ: Apropos weapons of mass destruction. As Iraq’s first minister of defense after the invasion, could you illuminate us as to what happened to them?

Allawi: It seems to be clear now that there was no serious Iraqi nuclear program in the wake of the U.N. inspections and that whatever had existed was either successfully dismantled or was just a bluff. The main issue is whether Iraq had the capability of developing weapons of mass destruction after the 1991 Kuwait war. It may have had that in 1989, and it probably came very close to it, maybe a few months or a few years at the most. But the removal of the key elements of the weapons program, together with the sheer difficulty of getting supplies and appropriate equipment, might have made the effort useless, and it was used primarily as a bargaining or threatening tool by Saddam. Whether or not this was known to the Bush administration, we will have to wait for some time before the smoking gun evidence emerges.

MEQ: Did the Iraqi government find any evidence of the existence of WMD or their possible removal out of the country?

Allawi: There is perhaps a general overestimation of Iraq’s ability to organize such a complex operation without access to the resources that Saddam had in the 1980s. The amount of money that came into Iraq then, some of which was used to fund this program, was simply not available in the 1990s. … I personally never thought back in the 1990s that there was a serious program. I thought it was a red herring.

MEQ: But then, how do you explain Saddam’s decision to risk total war? Given his all consuming paranoia and utter conviction that the Americans, among others, were out to get him, why didn’t he simply let the inspectors into Iraq and let the whole world see that he had nothing to hide?

Allawi: There are a lot of inexplicable decisions on Saddam’s part. I still cannot understand why he sent his air force to Iran during the 1991 Kuwait war, why he didn’t withdraw from Kuwait when it became clear that the coalition was going to attack, or why he persisted in goading the Americans [in 2003] into an irreversible decision. These decisions could have been made by a paranoiac. But they could also have been made by a man who never understood the strategic or the geostrategic circumstances in which he operated, and there were not enough people around him who had the courage to explain to him otherwise. So, there was an element of paranoia but also an element of ignorance of how Western policymakers, especially in America, make decisions and stick to them. He saw things mainly in terms of the crude conclusions about human nature he derived from his upbringing and life experience. It’s like a street fighter’s version of how events play out on the international scale. He was basically a brute, a very intelligent brute.

MEQ: Still, this brutish worldview kept him in power for longer than any other ruler in Iraq’s modern history and made war the only viable option to remove him.

Allawi: The war came as a direct consequence of 9/11. Had there been no 9/11, American foreign policy was unlikely to have shifted this way. Could sanctions have brought this regime down? The answer is no, clearly not. Could the Iraqi opposition have achieved anything against Saddam? The answer is also no. Could a war triggered by supporting insurgents in Kurdistan spread to the rest of the country? The answer is clearly no. So from the Iraqi opposition’s point of view, it was really an extraordinary event that overthrew Saddam. Looking back, I think it was rather futile to try to do it after the 1980s.

MEQ: So perhaps the war’s “accidental” origin explains its catastrophic aftermath.

Allawi: What struck me most was the incoherence of American policy. It just doesn’t make sense to undertake action of this size and scope—in some ways, very outlandish in terms of post-World War II international relations—only to allow that massive effort to deteriorate, like water slipping through your hand. The Americans really had only two choices: either to take responsibility for the consequences of the invasion and, therefore, manage the country until they changed its political culture, or to say, “We came here for this specific purpose; we have done this job. There are no weapons of mass destruction. The ideal of changing Iraq’s political culture has never been on the agenda. It’s time for us to get out.”

MEQ: How do you assess what took place?

Allawi: I know that Iraq is not Panama or Grenada, but it really got the worst of all worlds: the destruction of whatever dysfunctional state had existed, without anything replacing it that is coherently meaningful; with massive expenditure of resources in an unplanned and uncoordinated way that could have, in a more determined way, played a fundamental part in changing the country’s political culture. It’s not that the Americans didn’t spend money; they spent more money on a per capita basis than they probably spent on the Marshall Plan. But it was just so misguided and so ill-directed and not pulled together in a coherent strategy, with people who were indifferent to the long-term evolution of the country’s institutions. That just doesn’t make sense.

MEQ: When did you come to this realization?

Allawi: These issues became clear to me in September-October 2003 when I first went back. I kept a diary, and I made some of these observations back then. I argued that it was all going to end up in tears since there was no real effort to transform the country’s institutions and political culture. Rather there was an attempt to build on a political culture that had not been thoroughly reformed at the root and branch with a pseudo-democratic superstructure attached to it without having a real chance of developing into a genuine, democratic culture. This, in turn, was bound to end up in a hybrid situation—a hybrid, authoritarian-democratic system with warped democratic institutions or supposedly representative institutions.

But the counterargument is that one was operating in a barren landscape. There were very few choices available to either the U.S., or the coalition, or the Iraqi exiles who came back into power, apart from the Kurds who had their long-standing, quasi-national organizations that rooted them in the country. Everything else had to be imported.

A Decentralized Iraq

MEQ: Let’s take the counterargument a step further. In The Occupation of Iraq, you cite King Faisal I, founding monarch of Iraq, as saying (in 1932) that “there is no Iraqi people inside Iraq. There are only diverse groups with no national sentiments.” Likewise, you have recently argued that Iraq “is not a nation, at least not in terms of the commonly understood definitions of a nation.”[4] Has nothing changed during this 90-year period?

Allawi: There is obviously a sense of “Iraqiness.” The Arabs do have a sense that they are together in a kind of a long-term marriage, so to speak, in the context of the boundaries of modern Iraq. But there is nothing reflecting this communality at the level of loyalty to shared institutions or laws or to an identity that all parties adhere to and consider important. All view this identity as a corollary of its association to their own exercise of power. Take the Islamist parties, for example: In 2005, they were pushing for a decentralized, federal region, but once they began to exercise undivided power, the emphasis changed to the old Iraqi centralized state. There really is no common vision on the part of the various groups that constitute Iraq as to where the country should go and what kind of identity and role it should have at the end.

MEQ: What you are pointing to has been an issue for a long time.

Allawi: Yes, this problem has existed since the creation of Iraq in 1921, and nothing seems to have changed in a significant way. Regimes come and go, and they emphasize this or that aspect of the country, but there is no continuity in building national institutions that are free of sectarian considerations and are fair to the general population. The Baathists have perhaps been the worst of the lot, and their legacy is possibly the most detrimental, not least since it is etched even on the minds of their bitterest opponents. Thus, those who came into power used the levers of the Baathist state to their advantage rather than to reform and dismantle them (though at the superficial level they were democratized). The only difference is that now people are using the central state’s huge powers for their own purposes rather than for Baath purposes or Saddam’s purposes. If you wanted to get a job in Saddam’s days you had to be a Baathist; now you have to be close to the group that controls the relevant ministry. For the ordinary person on the street, nothing much has changed.

MEQ: You have recently argued that “there is nothing sacrosanct or inevitable about the survival of the Second Iraq State [i.e., post-Saddam Iraq]” and that “Iraqis must understand that this time around, the house may very well fall down on their heads if they don’t find a way of living together and enjoying being together.”[5] Could you elaborate?

Allawi: This is the last fling of the Second Iraq State. If the political caste doesn’t come up with something that takes into account the huge changes and opportunities that arose as a result of the destruction of the old dictatorial state, their hold on power will drastically diminish and dissolve, and the state may not last beyond the next cycle. Something else may come up.

MEQ: Are you saying that Iraq may disintegrate into a number of smaller states?

Allawi: I don’t think so. It remains to be seen how Iraq will be configured—as a centralized state, as a binational state, a confederation, or as something in between. The jury is still out on that.

MEQ: What’s your preference?

Allawi: I would build the state along the lines of a decentralized, federal system where a great deal of responsibility is put on the provincial and local authorities, who are in many ways closer to the people than the distant ministry in Baghdad, rather than repeat the buildup of the central state whose forms were basically outlined in the 1920s. This is because Iraq as a centralized state cannot really function in the long run unless there is high degree of political maturity or a dictatorship. There is just no way around it.

MEQ: Why not?

Allawi: What exists now is, again, the worst of all worlds. There are central ministries trying to enforce their dysfunctional authority on provincial powers that haven’t built up any institutional depth, with a Kurdish region that for all intents and purposes is on its own. And if you superimpose on this state of affairs electoral cycles of four or five years, manipulated by rulers seeking to perpetuate their power, then the state will disintegrate were it not for the oil revenues. If you take oil out of the equation, Iraq is one of the poorest states in the world. But with oil coming in, there will be a lot of expansion. This kind of ramshackle system might continue, but it is like a car or a machine operating at a much lower level than it is designed for.

You can read the rest of this fascinating interview at The Middle East Quarterly Review.