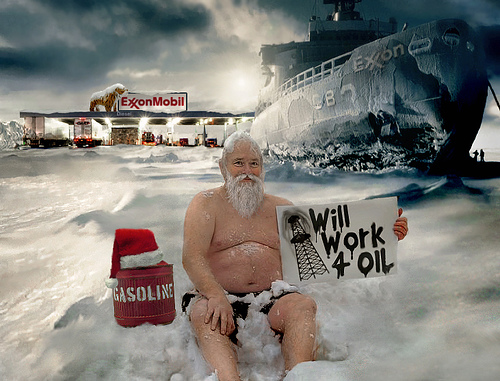

Black Ice: The Dangerous Race For Oil At The Top Of The World

Please note that we are not authorised to provide any investment advice. The content on this page is for information purposes only.

The world’s biggest oil and gas companies are competing for the enormous reserves of natural gas and oil in the Arctic, but the ecological and economic consequences of a major oil spill would be catastrophic.

The rush to explore the Arctic’s enormous oil and gas reserves is both hypocritical and absurd, says Rod Downie, Polar Policy and Programme manager at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) UK.

The world’s biggest oil and gas companies are competing for the enormous reserves of natural gas and oil in the Arctic, but the ecological and economic consequences of a major oil spill would be catastrophic.

The rush to explore the Arctic’s enormous oil and gas reserves is both hypocritical and absurd, says Rod Downie, Polar Policy and Programme manager at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) UK.

“In the UK, we are committed to legal targets with big reductions in carbon emissions of 80 percent by 2050 in our Climate Change Act. Globally, at the UN climate change summit in Cancun in 2010, 194 nations committed to a less than 2°C rise in temperature…

[quote]“But to achieve those international targets, over 80 percent of all known oil and gas reserves has to stay in the ground. And if we can only take out 20 percent of what remains, going ever deeper into more remote locations will be absurd and illogical,” Downie exclaims.[/quote]Yet the risk of looking stupid has rarely ever deterred a company from trying to earn a quick buck; and with oil and gas supplies running out in more accessible places, the world’s top oil companies – aided by Arctic governments willing to supply licences – are now clamouring for their share of the reserves at the top of the world.

The energy companies are well aware of the Arctic’s energy. According to an estimate by the US Geological Survey, the Arctic may contains 30 percent of the planet’s undiscovered natural gas reserves and around 160 billion barrels, or 13 percent, of its undiscovered oil.

Most of the reserves are thought to be in less than 500 metres of water, though the oil and gas are in different locations. The three areas thought to contain the most amount of oil are Alaska, the Amerasia Basin and the East Greenland Rift Basins; while more than 70 percent of the natural gas supply is likely to be found in three provinces: The West Siberian Basin and the East Barents Basins (both of which are in Russia), and Alaska, in the US.

Drawn by this major potential, all the oil giants are now trying their luck in the North.

British multi-national energy company BP for instance is one of the biggest players in the race for cold black gold, despite its catastrophic experiences last year in the Gulf of Mexico – when the Deepwater Horizon oil spill leaked around five million barrels of crude oil into the ocean.

Related: Oil Slickonomics – A Realistic Analysis of Gulf Disaster Impact from US Energy Investor

Related: Oil Spill Debacle Encapsulates Obama’s Structural Flaws

BP has a joint venture agreement with Russian energy firm Rosneft to exploit potentially huge deposits of oil and gas in the Arctic continental shelf; and the two firms have agreed to jointly explore three areas of Russian territory – known as EPNZ 1,2,3, and covering 125,000 square kilometres in an area of the South Kara Sea – for the coveted oil. A further US$10 billion is expected to be spent developing onshore oilfields in the autonomous Yamal-Nenets area of Russia.

Meanwhile, Scottish company Cairn Energy lost US$942 million last year in a failed attempt to find oil off the coast of Greenland. The futile pursuit was the main reason behind Cairn’s US$1.2 billion loss for 2011, though chairman, Sir Bill Gammell, has vowed to continue the quest this year.

Across the Atlantic in the United States, Shell also has plans to begin drilling up to six shallow water exploratory wells in the Chukchi Sea – 70 miles off the northwest coast of Alaska – in June. The US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement approved the firm’s oil spill response plans in February this year.

But perhaps the largest offshore Arctic energy project remains the development of the huge Shtokman gas field, which lies 350 miles into the Russian-controlled part of the Barents Sea. The consortium of three companies exploiting the site is made up of Gazprom from Russia, French energy giant Total SA, and Norwegian energy company Statoil. According to some estimates, the field could contain around 3.8 trillion cubic metres of natural gas and more than 37 million tons of gas condensate, with the expected investment into the project to reach US$50 billion.

Not surprisingly, the scramble for oil, which appears to put money before the long-term good of the planet, has angered many experts. Veteran arctic commentator Professor Oran Young, a former vice-president of the International Arctic Science Committee, said:

[quote]“They are trying to continue along the business-as-usual trajectory as long as possible. We can’t stop using oil overnight, but we should be proceeding more vigorously with the development of alternatives rather than continuing to the last gasp of the hydrocarbon economy.”[/quote]Even without the damage to the environment, the financial risks are not necessarily viable, added Professor Young.

“Arctic oil and gas will be expensive to transport to market so its attractiveness will be sensitive to fluctuations in the world market. Production and transport costs for Saudi oil, for example, will be around a quarter of the same costs for Arctic oil,” he said.

“The melting icecaps are making it easier to transport the oil, and a fully loaded oil tanker did make a passage through the Northern sea route last summer demonstrating the feasibility of doing that. But navigation in the Arctic is still a tricky proposition and there’s obviously a very black irony in going in for oil because global warming has caused the icecaps to melt.”

Lloyd’s of London, the world’s biggest insurance market, has also cast doubt on the business case for Arctic oil and gas. In a recent paper, the City firm estimated that US$100 billion of new investment was heading for the Far North over the next decade. But the report’s authors, Charles Emmerson and Glada Lahn of Chatham House said that cleaning up an oil spill, particularly in ice-covered areas, would present “multiple obstacles, which together constituted a unique and hard-to-manage risk.”

Richard Ward, Lloyd’s chief executive, urged energy companies not to “rush in [but instead to] step back and think carefully about the consequences of that action” before the right safety measures were in place.

[break]Cold Black Hearts For Cold Black Gold?

The authors of the Lloyd’s report included the likely damage to Arctic ecosystems in their overall assessment of the balance of risks and rewards. They said it was “highly likely” that drilling for oil and gas would further disturb ecosystems already stressed by climate change.

“Migration patterns of caribou and whales in offshore areas may be affected. Other than the direct release of pollutants into the Arctic environment, there are multiple ways in which ecosystems could be disturbed, such as the construction of pipelines and roads, noise pollution from offshore drilling, seismic survey activity or additional maritime traffic as well as through the break-up of sea ice,” the report said.

An additional complication, the Lloyd’s authors suggested, was the unclear legal boundaries posed by a complex tangle of regulations and separate Arctic governments. The Lloyd’s report pointed out that there was no international liability and compensation regime for oil spills.

And the catastrophic effects of an Arctic oil spill – potentially far worse than in the Gulf of Mexico – are not mere hypothesises. There has already been a test case in the Arctic – the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil tanker spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska, which resulted in the contamination of 1,300 miles of shoreline.

“The ecological and economic impacts were enormous,” said the WWF’s Downie, who gave evidence to a recent British Government inquiry into protecting the Arctic.

[quote]“Our 2009 report showed that even after a clean-up operation involving more that 10,000 people and 100 aircraft, oil was still found on beaches and intertidal zones, and up to 450 miles further afield. [/quote]“The oil continued to harm local wildlife, commercial fishing activities, coastal community cultures and the recreation and tourism industries,” he added.

Scientists estimate that over 80,000 litres of oil from the Exxon Valdez spill still remain on the beaches of Prince William Sound after more than 20 years.

“Oil that seeped deep into the mussel beds and boulder beaches can pollute the area for decades as subsurface oil can remain un-weathered and toxic for years before winter storms, or foraging animals, reintroduce it into the environment,” warned Downie.

The WWF report highlighted the extent of the ecological disaster in Alaska: Dead wildlife included around 250,000 seabirds, nearly 4,000 sea otters, 300 harbour seals, 250 bald eagles and more than 20 orcas. The oil also destroyed billions of salmon and herring eggs; and in financial terms, the Exxon Valdez left a huge trail of destruction. The WWF report estimates that Alaska suffered US$20 billion in subsistence harvest losses, US$19 million in lost visitor spending in the year following the spill, as well as at least US$286.8 million in losses to local fishermen.

The major impediments to a clean-up project in the Arctic back then, and even today, was the geographical remoteness of the area and the harshness of the climate, which made the region inaccessible for large periods of time.

[quote]“Because it’s so remote, the physical infrastructure is not there. There is a lack of trained people on hand to deal with a spill and it would take a long time to get oil spill teams out there,” said Downie.[/quote]WWF’s Canadian office has also studied the Arctic “response gap”, which is the percentage of the year when no response to a spill is possible due to environmental conditions in Arctic Canada’s offshore regions.

According to their research, any oil spill response in the Beaufort Sea during the month of June will be impossible to conduct 66 percent of the time for a location near offshore, and 82 percent of the time for somewhere far offshore. A spill response in the same area would also not be possible for more than 50 percent of the time between June and September. By October, no response would be possible for more than four-fifths of the time, while there is a next to zero percent chance of a response from November to May. Oil spill response gaps must be factored into the assessment of the potential consequences of a blowout, or spill at proposed drilling locations, according to the WWF.

“Not only is it inhospitable terrain, but the ice and snow also absorb oil which massively increases the amount of material you need to clean up,” said Downie. “Sea ice is a dynamic, moving thing. In the event of a major spill, Arctic sea ice would act like a massive piece of blotting paper, moving around the Arctic smearing everything in its path.”

“If an area is particularly biologically important to them, the animals may refuse to move elsewhere if a disturbance occurs, and may be harmed as a result,” added Downie. “Cetaceans also use sound to communicate, navigate and feed, and the noise produced by offshore oil and gas operations is of real concern. Adverse effects can include hearing loss, stress, discomfort and injury.”

What’s more, exploratory drilling will generate large volumes of mud and cuttings that are discharged into the sea, which can have an ecological impact on phytoplankton and zooplankton – resulting in greater pressure for the entire ecosystem.

But oil companies cannot be held solely responsible for any ecological dangers, says Professor Young. The National governments who are granting licences in an apparent contradiction of pledges to reduce emissions also must share some responsibility.

[quote]“It’s a complex business. There are a lot of ambivalent feelings in the Arctic communities about oil and gas,” said Professor Young. “The natives are very concerned about the environmental impacts, but the drilling also means jobs and stimulates the economy.”[/quote]“The best example is Greenland, where the 57,000 natives long for independence from Denmark, but rely on a US$600 million handout each year, which is 55 percent of the island’s budget.”

“For Greenland, the idea of becoming independent from Denmark isn’t realistic without some greater source of financial support. The injection of money from oil revenues has already allowed them to think more about autonomy, but there are deeply mixed feelings about oil in Greenlandic politics and similar issues are being discussed in Canada and Alaska,” he added.

Related: Oil Spills

Related: Green Growth Or De-Growth: What Is The Best Way To Stop Businesses Destroying The Biosphere?

Larger nations than Greenland, however, can have a say in what happens in the Arctic. Nevertheless, the US Government recently licensed the operations of Shell in Alaska and the UK has allowed Cairn Energy and BP to drill in the Arctic.

[quote]“British PM David Cameron boasted that his would be the ‘greenest government ever’, but we see no evidence of that,” says Downie. “Of all the non-Arctic nations, the UK has the biggest interest, but we don’t even have a coherent Arctic strategy.” [/quote]